Corruption laws in Bangladesh and Anti-Bribery Laws

Corruption has always been a major concern for Bangladesh, as it has a direct impact on the country’s economy and development. Bangladesh has certainly been successful in reducing the level of corruption over the past few years as a result of its efforts to prevent corruption by implementing numerous stringent laws.

A corruption or bribery allegation is one of the quickest ways to tarnish a company’s reputation. While corporations conducting business in Bangladesh have their own anti-corruption and anti-bribery policies and compliance programs, an evaluation of Bangladesh’s anti-corruption and anti-bribery laws is of utmost importance. The purpose of this paper is to provide an overview of the legal and regulatory framework in effect in Bangladesh.

Bangladesh’s applicable anti-corruption and anti-bribery statutes

The Prevention of Corruption Act of 1947 (PCA 1947) was the very first special law to be implemented in Bangladesh to combat bribery and corruption. The Bangladesh Anti-Corruption Act of 1974 (“BAC 1974”) was subsequently enacted, establishing the Bureau of Anti-Corruption to combat and control bribery and other forms of corruption. BAC 1974 was repealed and replaced by the Anti-Corruption Commission Act of 2004 (ACCA 2004).

The Anti-Corruption Commission was established by the Anti-Corruption Act of 2004, and the Bureau of Anti-Corruption established under the Anti-Corruption Act of 1974 was dissolved as a result. However, notwithstanding anything stated in any other law, the Penal Code 1860 (“PC 1860”) also covers a number of offenses that are directly or indirectly related to corruption and bribery and are therefore subject to the Act. In addition, the Government has enacted the Anti-Money-Laundering Act of 2012 and various other laws to combat corruption and bribery-related offenses.

Definition of corruption and bribery within Bangladesh’s jurisdiction

Corruption

In neither ACCA 2004 nor PC 1860 is a comprehensive definition of corruption provided. Instead of providing a general definition, section 2(E) of the ACCA 2004 referred to certain offenses listed in the ACCA 2004 schedule and stated that they were to be considered corruption offenses. According to the schedule, the following offenses are defined:

- Offenses under sections 161 (Public servant taking gratification other than legal remuneration in respect of an official act), 162 (Taking gratification in order, by corrupt or illegal means, to influence public servant), 163 (Taking gratification for exercise of personal influence with public servant), 164 (Punishment for abetment by public servant of offences defined by sections 162 or 163), 165 (Public servant obtaining valuable thing, without consideration, from persuader),

- Offenses under sections 420 (Cheating and dishonestly inducing delivery of property), 467 (Forgery of valuable security, will, etc.), 468 (Forgery for the purpose of cheating), 471 (Using as genuine a forged document), and 477 (Fraudulent cancellation, destruction, etc., of will, authority to adopt, or valuable security) if such offenses involve public property or are committed by government employees, employees of banking institutions, or employees of insurance

- Infractions outlined in the Prevention of Corruption Act of 1947.

- Infractions listed in the Money Laundering Prevention Act of 2012

- All the offenses listed above in connection with and in relation to the offenses listed in Sections 109 (Punishment of abetment if the act abetted is committed as a result and where no express provision is made for its punishment), 120B (Punishment of criminal conspiracy), and 511 (Punishment for attempting to commit offenses punishable by life imprisonment or imprisonment) of the PC 1860.

In addition, the PC 1860 lacked a definition of corruption and instead defined “wrongful gain.”

According to PC 1860, wrongful gain is the unlawful acquisition of property by a person who is not legally entitled to it. On the basis of this definition, violations of sections 161-169, 171, 217-218 and 409, as well as sections 420, 467, 468, 471 and 477, if such violations involve public property or if such violations are committed by government employees or employees of banking institutions or employees of financial institutions while performing official duties, fall within the scope of the common corruption offenses.

Bribery

The PC 1860 provides a comprehensive outline of what acts may constitute bribery.

According to section 23 of the Criminal Code of 1860, bribery is committed by anyone who gives a gratification with the intent of inducing or attempting to induce another person to exercise an electoral right, or accepts a gratification as a reward for exercising such a right, or for inducing or attempting to induce another person to exercise such a right.

Whoever commits the crime of bribery shall be punished by imprisonment of either kind for a term that may not exceed one year, a fine, or both. However, it has also been stipulated that bribery by gift shall only be punished by a fine.

Punishment under the Criminal Code of 1860

If a public servant accepts, obtains, or attempts to obtain any gratification other than legal remuneration as a motive or reward for doing any official act, or for showing favor or disfavor to any person, or for rendering any service or disservice to any person, this shall be considered an offense, and the public servant shall be punished with imprisonment of either description for a term that may not exceed three years, or with fine, or with both.

According to said PC 1860, the term ‘gratification’ is not limited to monetary or monetary-estimable gratifications. In addition, “legal remuneration” is not limited to remuneration that a public servant can legally demand, but includes all remuneration that his employing authority permits him to accept.

Similarly, taking gratification to influence a public servant, taking gratification for exercising personal influence with a public servant, obtaining valuable things by public servant from person involved in proceeding or business transacted by such public servant, disobeying law or framing an incorrect document by public servant with intent to cause injury to any person or public servant unlawfully engaging in trade or purchasing or bidding for property or any accomplice(s) to s.

In addition, whoever accepts or attempts to obtain any gratification for himself or any other person, or any restitution of property, in exchange for the concealment of an offence under his/her screening of any person from legal punishment for any offence, shall, if the offence is punishable with death, be punished with imprisonment of either description for a term which may extend to seven years, and shall also be liable to a fine; and if the offence is punishable with life imprisonment, be punished.

The same type of punishment has been imposed on the individual who provides the money, benefit, or satisfaction.

The Prevention of Corruption Act’s scope

The PCA 1947 provides neither a definition nor identifies the criteria for what constitutes corruption or bribery. However, the PCA 1947 has designated certain offenses as “criminal misconduct” and outlined their maximum penalties.

The offenses designated as criminal misconduct under the PCA 1947 are identical to those listed in Section 161-165 of the PC 1860, as stated above. However, the maximum punishment prescribed by PCA 1947 is greater than the maximum punishment specified by Penal Code 1860.

For instance, the maximum punishment for committing an offense under section 161 of the PC 1860 is three years in prison, a fine, or both; however, the maximum punishment for committing a similar offense under section 5(1) of the PCA 1947 is seven years in prison, a fine, or both. As the PCA 1947 is a specialized law, however, the punishment prescribed by said act shall take precedence over others.

Implications of the 2004 Anti-Corruption Commission Act

Establishment of the Commission

The ACCA 2004 focuses primarily on the composition and duties of the Commission. The Commission shall have the authority, among other things, to inquire and investigate corruption-related offences, to file and conduct cases under this Act based on its own inquiries and investigations, to inquire into any allegation of corruption on its own initiative or upon an application filed by an aggrieved person or by any person on his/her behalf, and to perform any other work deemed necessary for the prevention of corruption, etc.

The authority to investigate and arrest

The Commission shall have the authority to summon witnesses, ensure their appearance, and question them under oath, to discover and present any document, to take testimony under oath, to issue warrants for the interrogation of witnesses and the examination of documents, and to deal with any other matter necessary to achieve the law’s goals and objectives.

In addition, the Commission may request information from any person in relation to any inquiry or investigation, and any such person is required to provide the information at his disposal.

However, the ACCA 2004 makes no provision for the resolution of possible conflicts arising from official secrets, legal and professional privilege, or banking privilege. Furthermore, the ACCA 2004 fails to state under what circumstances such privileged/protected documents will be subject to disclosure to the Commission or what safeguards will be provided for such documents when they are produced for examination by the Commission.

In order to conduct an investigation, the Commission may authorize a subordinate officer of the Commission to investigate corruption with the authority of a police station’s officer in charge.

Moreover, notwithstanding any other provision of the aforementioned ACCA 2004, if any officer empowered by the Commission has justifiable reasons to believe that a person in his/her name or in the name of others is the owner or in possession of moveable or immovable property that is not compatible with his/her known and declared sources of income, the officer may arrest that person, subject to court permission.

However, the statute does not specify the circumstances under which such a person may be arrested, nor its purpose or duration.

Declaration of attributes

If the Commission is satisfied based on its own information and necessary investigation that any person or any other person on his behalf is in possession or has obtained ownership of property not consistent with his legal sources of income, then the Commission shall, through a written order, require that person to submit a statement of assets and liabilities in the manner determined by the Commission and to furnish any other information specified in that order.

If any person, after receiving such an order, fails to submit a written statement or provide the requested information, or if that person submits a written statement or provides information that is false or fictitious, or if there are sufficient grounds to doubt their veracity, or if that person submits any book, account, record, declaration, return, or document, or if that person gives a statement that is false or fictitious, or if there are sufficient grounds to doubt its veracity,

Possession of property in proximity to the identified sources of income

If a public official is found to be in possession of property or liquid assets that he should not have received by law or that are inconsistent with the known sources of his income, then such illegal possession of assets shall be considered a corruption offense, and if proven guilty, the public official may be punished with imprisonment for a minimum of three (3) years and a maximum of ten (10) years, as well as a fine of up to ten thousand (10,000) BDT.

In addition, if it is proven during the trial of charges that the accused person in his own name or any other person on his/her behalf has obtained ownership or is in possession of moveable or immovable property inconsistent with his/her known sources of income, the court shall presume that the accused person is guilty of the charges, and unless the person rebuts that presumption in court, the punishment meted out on the basis of this presumption shall not be unlawful.

Amendments to the Anti-Corruption Commission Act of 2016

In 2016, the Bangladeshi government enacted the Anti-Corruption Commission (Amendment) Act 2016. According to the 2016 Amendment Act, Sections 408 (Criminal breach of trust by clerk or servant), 420 (Cheating and dishonestly inducing delivery of property), 462A (Penalty for negligent conduct of bank officers and employees), 462B (Penalty for defrauding banking company), 466 (Forgery of record of Court or of public register, etc.), 467 (Forgery of valuable security, will, etc.),468 (Forgery

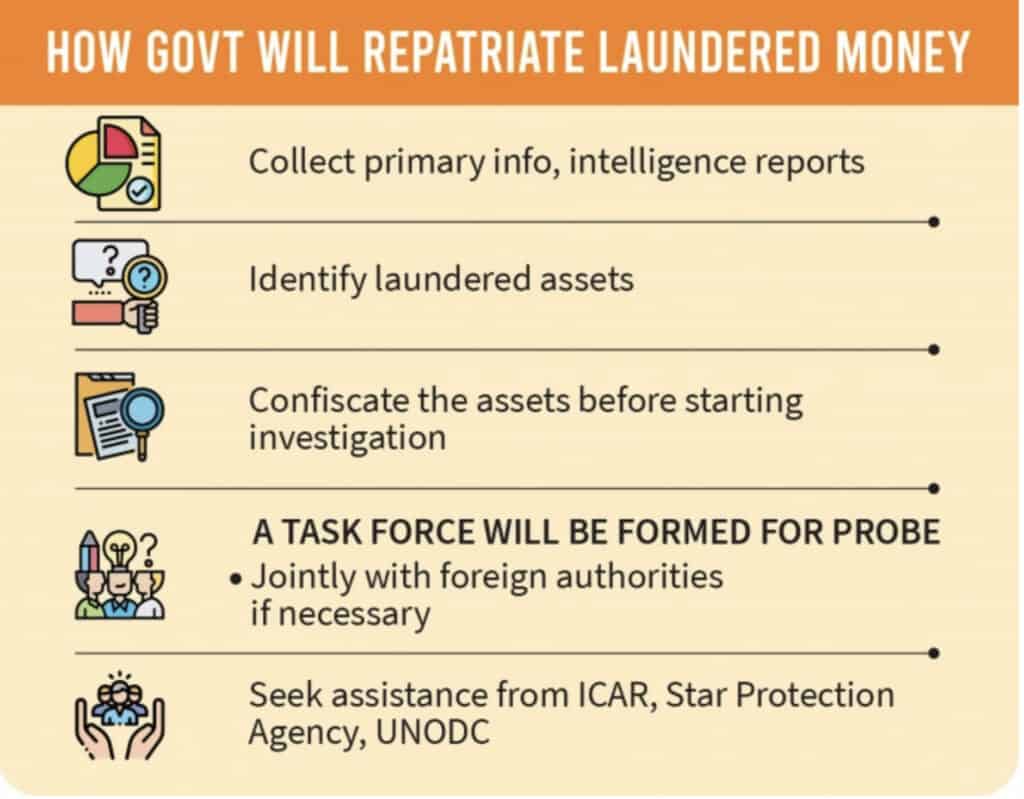

Corruption and laundering of funds

The Money Laundering Act, 2012 (“MLA 2012”) criminalizes the illegal transfer of assets derived from “predicate offenses” from Bangladesh to any other country or vice versa, as well as the conversion of such assets with the intent to conceal the source of the earnings. In accordance with the MLA 2012, both individuals and corporations can be held accountable for bribery.

A person who violates the MLA 2012 is subject to imprisonment for a term of at least 4 (four) years and no more than 12 (twelve) years, as well as a fine equivalent to twice the value of the property involved in the offense or taka 10 (ten) lacks, whichever is greater. Nonetheless, if an entity violates the MLA 2012, it will be subject to a fine of not less than twice the value of the property or taka 20 lacs, whichever is greater, and its registration may be revoked.

| Question | Answer |

|---|---|

| 1. What is the legal framework for anti-corruption in Bangladesh? | The legal framework for anti-corruption in Bangladesh is primarily based on the Anti-Corruption Commission Act, 2004, which established the Anti-Corruption Commission (ACC) as an independent statutory body with the power to investigate and prosecute corruption offenses. |

| 2. What are the penalties for corruption in Bangladesh? | The penalties for corruption in Bangladesh can range from fines to imprisonment, depending on the nature and severity of the offense. For example, under the Prevention of Corruption Act, 1947, the maximum punishment for bribery is seven years imprisonment and a fine. |

| 3. What is the legal framework for anti-money laundering in Bangladesh? | The legal framework for anti-money laundering in Bangladesh is primarily based on the Money Laundering Prevention Act, 2012, which established the Bangladesh Financial Intelligence Unit (BFIU) as the central agency for receiving, analyzing and disseminating financial intelligence to prevent money laundering and terrorist financing. |

| 4. What are the penalties for money laundering in Bangladesh? | The penalties for money laundering in Bangladesh can range from fines to imprisonment, depending on the nature and severity of the offense. For example, under the Money Laundering Prevention Act, 2012, the maximum punishment for money laundering is 12 years imprisonment and a fine of BDT 1 crore (approximately USD 120,000). |

| 5. What is the role of the Bangladesh Bank in anti-money laundering efforts? | The Bangladesh Bank is responsible for ensuring that all financial institutions in Bangladesh implement effective anti-money laundering measures, and for monitoring their compliance with the relevant laws and regulations. |

| 6. What is the process for reporting suspicious transactions in Bangladesh? | Financial institutions and designated non-financial businesses and professions (DNFBPs) are required to report suspicious transactions to the BFIU, which then analyzes the information and disseminates it to relevant law enforcement agencies for further investigation. |

| 7. What is the legal status of whistleblowers in Bangladesh? | Whistleblowers are protected under the Whistleblower Protection Act, 2011, which provides legal protection to individuals who report corruption and other illegal activities. |

| 8. How does Bangladesh cooperate with other countries in anti-corruption and anti-money laundering efforts? | Bangladesh is a member of the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) and the Egmont Group of Financial Intelligence Units, and cooperates with other countries and international organizations in sharing information and coordinating anti-corruption and anti-money laundering efforts. |

| 9. How does the government of Bangladesh ensure the independence of anti-corruption and anti-money laundering agencies? | The Anti-Corruption Commission and the Bangladesh Financial Intelligence Unit are both established as independent statutory bodies with a mandate to operate independently of the government. The heads of these agencies are appointed by the President of Bangladesh on the recommendation of a selection committee. |

| 10. What is the role of civil society organizations in anti-corruption and anti-money laundering efforts in Bangladesh? | Civil society organizations play an important role in raising public awareness about corruption and money laundering, advocating for reforms, and monitoring the implementation of anti-corruption and anti-money laundering measures. Some organizations also provide support and protection to whistleblowers and other individuals who report corruption and other illegal activities. |

The proper implementation of anti-corruption and anti-bribery laws will depend largely on the Commission’s role. On paper, the Commission has been granted extensive authority to combat corruption with minimal interference and obstruction. In the past, political influence has played a significant role in manipulating the Commission to meet its needs. Therefore, an impartial and independent Commission is required to eradicate corruption in Bangladesh.

The ‘Anti Corruption Commission (Amendment) Bill 2013’, which was passed on 10 November 2013 and includes a new provision requiring prior government approval to file corruption cases against public servants, is one of the loopholes in this war on corruption.

The amendment proposed a new provision in section 32 of the ACC (Anti-Corruption Commission) Act of 2004, which would require the commission to follow Rule 197 of the Criminal Procedure Code (CrPC) when prosecuting a judge, magistrate, or public servant.

Rule 197 of the CrPC states that when a judge within the meaning of section 19 of the Penal Code, a magistrate, or a public servant who is not removable from his office except by or with the sanction of the government is accused of any offence alleged to have been committed by him while acting or purporting to act in the discharge of his official duty, no court shall take cognizance of such an offense without the prior sanction of the government.

In January 2014, however, the Honourable High Court of Bangladesh ruled that the most recent amendment was unconstitutional because it limited the authority of the ACC. A HC (High Court) division bench struck down the relevant section 32 (A) of the ACC (Amendment) Act of 2013 in response to a writ petition.

The Bangladeshi government passed the Anti-Corruption Commission (Amendment) Act in 2016. According to the Amendment Act of 2016, Section 408, 420, 462A, 462B, 466,467,468, 479, 471 and 477A of the Penal Code 1860 shall not be triable under Section 28 of the ACC Act 2004 except in cases where the alleged property is a government property, or the alleged person is a government official while discharging his official duties, bank-employees or employers, employees or employers of any financial institution.

According to the amendment, any accusations under the above-mentioned sections of the Penal Code, except in cases where the alleged property is government property or the alleged person is a government official while discharging his official duties, bank employees or employers, or employees or employers of any financial institution while discharging his official duties, shall be dealt with in accordance with standard procedure.

The Government Servant (Conduct) Rules, in addition to the ACCA 2004, the Code of Criminal Procedure, the Prevention of Corruption Act, the Penal Code, and the Money Laundering Prevention Act, play significant roles in the fight against corruption.

The Bangladeshi law firm Tahmidur Rahman Remura Wahid and its litigation department

Tahmidur Rahman Remura Wahid is an all-encompassing law firm. One of our primary areas of practice is anti-corruption law. We have a team of seasoned attorneys with extensive experience in corruption, bribery, and corporate criminal law.

We have advised and collaborated with the World Bank and IFC on the publication of multiple reports on the anti-corruption and bribery laws of Bangladesh. For various projects, we have assisted foreign law firms in conducting research on Bangladeshi anti-corruption and bribery laws (i.e. overseas corruption project of the Clifford Chance LLP).

We have represented a number of corporations, individuals, and government/public organizations in Anti-corruption Commission (ACC) proceedings involving anti-corruption and corporate criminal activity.

In addition, we have represented various corporate clients in corporate criminal proceedings before the Company Bench of the High Court Division, the Labour Court and Appeal Tribunal, and other courts of competent jurisdiction.

Our foreign clients include the portfolio of American Express, Associated British Foods, Baker Hughes Incorporated, Bank of America, Bank of New York Mellon, Barclays Bank PLC, BG International Limited, BP America Inc, Cerberus Capital, Citi Bank, Credit Suisse, Fidelity, Goldman Sachs & Co, JP Morgan, MasterCard International, McGraw Hill Financial Inc., Guggenheim Partners, Morgan Stanley, Royal Bank of Scotland, UBS, Wells Fargo & Company.

GLOBAL OFFICES:

DHAKA: House 410, ROAD 29, Mohakhali DOHS

DUBAI: Rolex Building, L-12 Sheikh Zayed Road

LONDON: 1156, St Giles Avenue, 330 High Holborn, London, WC1V 7QH

Email Addresses:

info@trfirm.com

info@tahmidur.com

info@tahmidurrahman.com

24/7 Contact Numbers, Even During Holidays:

+8801708000660

+8801847220062

+8801708080817