State to State Arbitration Process

Arbitration has been defined as “a third-party dispute resolution mechanism that typically results in an award binding on the arbitration parties.” State-to-state arbitration is based on the parties’ mutual will and has been defined as “the resolution of differences between States by judges of their own choosing and on the basis of respect for law.”

It is similar to international court proceedings in that it requires the parties’ consent, though the time at which consent is provided and the scope of the consent can vary significantly.

An undertaking to arbitrate can result from an agreement to arbitrate before or after a dispute arises, and it is based on legal obligations that must be fulfilled in good faith. State-to-state arbitrations differ from general commercial arbitrations in that they may include political considerations as well as purely commercial issues.

Arbitration is similar to the court system in some ways. Similarly to the Court, an arbitrator is a judge who participates in the arbitration process. However, an arbitrator is a neutral third party chosen by both parties who is primarily responsible for resolving the dispute between the parties.

After hearing the claims and scrutinizing the supporting documents, the arbitrator renders a decision on the disputed matter. To avoid unintended consequences, the parties involved can file their claim on their own or hire an expert in this field.

The numerous benefits are the primary reasons for Arbitration’s growing popularity. Some of the key benefits of hiring an arbitrator in Bangladesh and choosing arbitration for dispute resolution are as follows:

Arbitrator Selection:

The parties involved in the dispute can choose an impartial person from the panel of arbitrators to serve as the arbitrator.

Convenient forum of hearing: The seat for arbitration can be chosen by the parties at their discretion.

Practical adaptability:

The parties or their lawyers can submit the necessary documents or evidence to support their claim in any pre-agreed-upon manner.

Confidentiality is one of the most important aspects of arbitration. Many parties are hesitant to settle a dispute in open court. Arbitration allows a small number of people to resolve a dispute, ensuring that the parties’ privacy is protected.

Quick: The arbitration process is much faster than the traditional court system.

Less expensive: The arbitration process is less expensive than traditional litigation.

In some ways, arbitration is like the court system. An arbitrator is a judge who takes part in the arbitration process, much like the court does. The primary responsibility for resolving the conflict between the parties, however, rests with an arbitrator, a neutral third party chosen by both parties.

The arbitrator makes a determination regarding the dispute after hearing the claims and reviewing the supporting documentation. The parties involved can file their claim on their own or hire a specialist in this field to avoid unintended consequences.

The main factors influencing arbitration’s rising popularity are its many advantages. The following are some of the main advantages of using arbitration to resolve disputes in Bangladesh:

Selection of the Arbitrator:

From the panel of arbitrators, the parties to the dispute may select an impartial individual to serve as the arbitrator.

Convenient place of hearing: The parties are free to choose the location of the arbitration.

Practical flexibility:

The parties or their attorneys may submit the required paperwork or proof of their case in any prearranged manner.

One of the most crucial aspects of arbitration is confidentiality. In open court, many parties are reluctant to reach a resolution. A dispute can be arbitrated by a small group of individuals, protecting the parties’ privacy.

Quick: Compared to the conventional court system, the arbitration process moves much more quickly.

Less expensive: Compared to traditional litigation, arbitration is more affordable.

The use of arbitration for resolving disputes involving foreign investments dates back to the time before investor-state arbitration under BITs gained popularity.

However, at the time, it may not have been the most popular method of dispute resolution because, given the size of the sums at stake, a court or judge would have preferred the parties to resolve the cases privately between themselves.

In the latter half of the eighteenth century, a number of ad hoc claims commissions and arbitral tribunals made decisions regarding the status of property owned by foreign nationals. Positive developments in this direction include a push for the idea of equal treatment for visitors and a commitment to refraining from meddling in the internal affairs of the host nation.

Even though the League of Nations made efforts, it wasn’t until the end of World War II that a significant international legal framework for the protection of investor rights was developed.

In documents like the OECD’s Draft Convention on the Protection of Foreign Property and the Havana Charter for an International Trade Organization, which failed to win international acceptance and did not go into effect after the Second World War, efforts were made to systematize the field of international economic law.

Through the 1959 Draft Convention on Investments Abroad, which sparked debate but never went into effect, efforts were also made outside of the government.

The Convention on the Recognition and Enforcement of Foreign Arbitral Awards 158 and the Convention on the Settlement of Investment Disputes between States and Nationals of Other States 159 were both signed in the interim, and among other significant developments, the UN General Assembly adopted the Charter of Economic Rights and Duties of States in 1974.

Expansion of IIA

The expansion of IIAs globally has encouraged research into the IIAs’ provisions. Numerous researchers have claimed that IIAs, especially BITs, exhibit a uniform nature and that a BIT’s provisions are set in stone.

However, opposing viewpoints point out that IIAs are frequently bilateral and that negotiations are conducted clause-by-clause, with significant portions of the IIAs having undergone new negotiations. As a result, the treaties that the parties negotiate differ significantly.

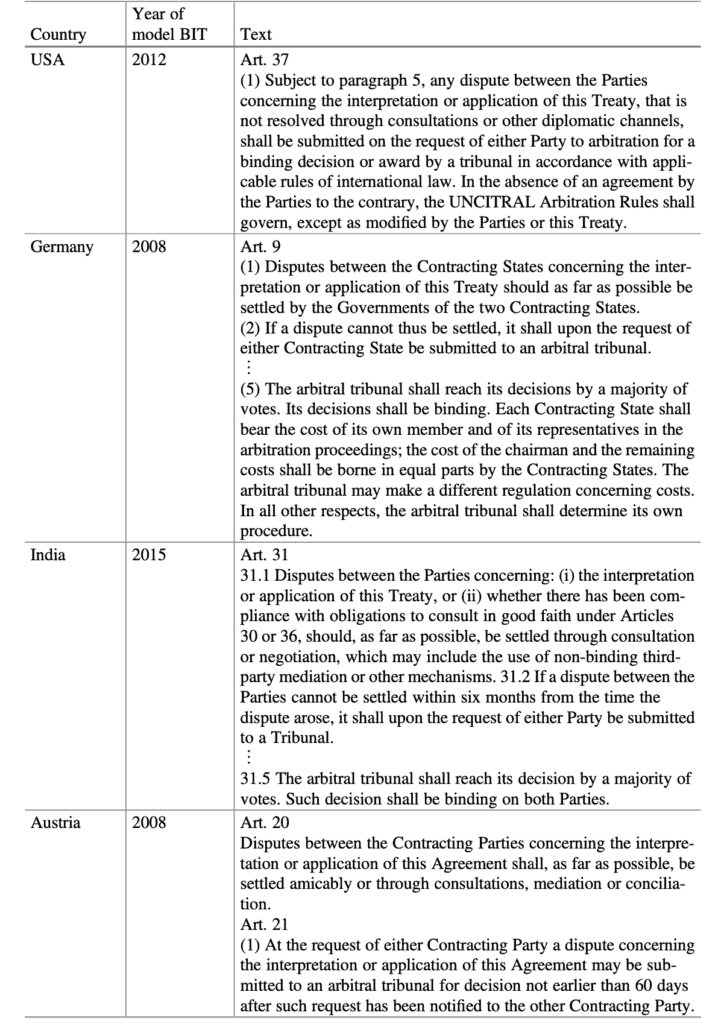

Even the dispute resolution provisions, which are regarded by some as the IIA’s most significant provision overall (163), differ from treaty to treaty by relatively small but significant margins.

While some treaties permit direct access to international arbitration, others are more conservative and demand that disputes be first resolved in domestic courts before being brought before investor-state arbitration. Another significant difference is whether a given treaty permits arbitration under the ICSID Convention, one of the most popular methods for resolving investment disputes.

Several trade agreements and other agreements with provisions for investment protection have been signed in recent years. The signing of trade agreements with an investment chapter, like the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) or a sector-specific agreement like the Energy Charter Treaty (ECT), is a growing trend among nations.

An indication of a potential return to the old Freedom, Commerce, and Navigation (FCN) treaty framework, which contained treaties with a broad scope, is the general increase in complexity of IIAs in the latter part of the twenty-first century as a result of the shift from straightforward BITs to trade and investment agreements.

Another trend is the development of particular BIT models that have been mandated by various nations and international organizations like the OECD.

Minor parameters such as liberalization, minimum standards under international law, and an emphasis on the individual also differ between the two main BIT models, the American and European BITs.

168 BITs have also been modified to include specific provisions or explanations, such as explicit provisions governing the application of the MFN Clause in dispute resolution clauses, among other things, in the UK-Ethiopia BIT of 2009169 and the annexure on the definition of indirect expropriation.

State to State Arbitration Under IIAs as a Dispute Resolution Mechanism

Arbitration and adjudication are the two most popular legal methods of dispute resolution. State-to-state arbitration and investor-state arbitration are both possible forms of arbitration in IIAs; however, the study primarily focuses on state-to-state arbitration.

State to State Arbitration in IIAs: Its History

One of the earliest references to arbitration can be found in the 1794 Amity, Commerce, and Navigation Treaty, which is where the compromissory clauses establishing state-to-state arbitration as a method of dispute settlement in modern IIAs have their roots.

The FCN treaties were mainly signed by the USA and mostly concerned business-related issues. The first FCN treaty was signed between the USA and France in 1778, and their history dates back to the eighteenth century.

The process of signing these treaties continued, with examples including the USA-Brazil FCN treaty in 1828, the USA-Germany FCC treaty in 1923 and later after the Second World War, the USA-Italy FCN treaty in 1948, the USA-Ireland FCN treaty in 1950, and the USA-Belgium Friendship, Establishment, and Navigation (FEN) treaty in 1961, to name a few.

After the Second World War, the FCN treaties expanded to include investment protection. They served as a model for the 1959 Draft Convention on Foreign Investments, which later became the modern BITs.

FCN treaties can still be used for investment claims, as demonstrated by the ELSI case, which was brought before the ICJ based on a breach of an FCN treaty based on the compromissory clause in the treaty. More than 40 FCN treaties are still in force, making them important on their own. Even in the midst of the discussion on investment arbitration based on IIAs.

The lessons learned from FCN treaties can also be applied to future investment treaty negotiations because they shed light on how to include a variety of topics in a single treaty and perhaps even non-economic issues like human rights.

They served as the American alternative to European BIT programs until the 1960s, with a much wider area of coverage than BITs, including human rights, intellectual property rights, and navigation rights.

The FCN treaty program was finally abandoned by the USA in 1968 as Europe advanced due to the competitive advantages provided by the BITs. 186 state-to-state arbitration clauses, now known as the compromissory clause, came to be integrated into BITs as a legacy from the FCN treaty program.

Since the first BIT was signed between Germany and Pakistan, state-to-state arbitration has been included in IIAs through compromissory clauses; as of now, all German BITs do as well.

The 1959 Draft Convention on Investments Abroad, also known as the Hermann-Shawcross Convention, contained a similar compromissory clause. Long after the first BIT with investor-state arbitration was concluded in 1968, a compromissory clause with state-to-state arbitration served as the only method of third-party dispute resolution in some IIAs until 1984–192.

However, the said compromissory clause has rarely drawn attention, a fact that can be attributed to the provision’s limited success and a common belief that it could only cover institutional issues of BIT interpretation or issues of racial discrimination.

State-to-state arbitration is a dispute resolution option in the WTO as well as most IIAs at the time of this study (occasionally as an option alongside other dispute resolution options like consultation, negotiation, or referral to international courts and tribunals). State-to-state arbitration (or litigation) is frequently the only means of binding dispute resolution in investment treaties, especially for nations with a large number of older treaties, like Germany or Switzerland.

In fact, state-to-state arbitration as a ‘binding’ form of dispute resolution is currently experiencing a resurgence with support from both states and investors, but as previously mentioned, very few investment treaties actually provide for recourse to ISDS. However, states parties to an IIA who have agreed to a compromissory clause with recourse to arbitration are required by law to conduct the arbitration in good faith as and when any disputes arise.

How the State to State Arbitration Process Works

The establishment of the state-to-state arbitral tribunal is a crucial step in the use of the compromissory clause under an IIA. The establishment of the SSAT marks the start of the second phase of the arbitration process, which consists of three phases: the execution of the agreement to arbitrate; the proceedings before the arbitrator; and the enforcement proceedings.

An arbitral tribunal established under international law is based on some instrument of international law, such as a treaty, which governs its operation. 61 The formation of the SSAT marks the start of the second phase.

The conclusion of an IIA with a compromissory clause mandating state-to-state arbitration already completes the first phase of an interstate arbitral process, and the third phase is largely outside the scope of this study. The second phase and main topic of this study, the operation of the arbitral tribunals, is covered in the following section.

Arbitrability as a Crucial Component of Arbitration

The word “arbitrability” is typically used to refer to the conditions or prerequisites that must be met in order for arbitration to proceed. The term refers to a number of matters, including inquiries regarding the existence of an arbitration agreement, its legality, and the scope of the dispute covered by the agreement.

The criteria for determining arbitrability are frequently used to highlight the challenges to arbitral jurisdiction that courts may take into account.

When it comes to international arbitration, it is up to the arbitral tribunal to decide whether a specific dispute can be arbitrated based on the law governing the contract and the arguments put forth by the parties.

Arbitration conducted in accordance with the Model Rules, which mandate that the ICJ determine whether a dispute can be arbitrated in the absence of a tribunal, is an exception to this rule. Due to increased recognition of the parties’ autonomy and the arbitral tribunal’s authority to make its own decisions, it is not anticipated that this provision will be used anytime soon.

Principles Relating to an Arbitral Tribunal’s Jurisdiction

The definition of jurisdiction is the “ability of a particular forum to hear a case.” The question of “who decides” whether an arbitral tribunal has jurisdiction in a particular case is debatable and is based on two doctrines: separability and competence-competence.

It is an assessment of whether the court or tribunal has the authority to decide on a case and render a decision that will be binding on the parties. Both of these tenets stem from the parties’ desire to advance arbitration as a method of resolving disputes.

The issue of whether an arbitral tribunal has jurisdiction over a dispute is typically resolved in three steps in cases of commercial international arbitration.

The first phase of the process may involve court proceedings with a request to refer the dispute to arbitration from one party; the second phase involves the arbitral tribunal determining its own jurisdiction; and the third phase involves a court’s determination of the tribunal’s jurisdiction in the event that the tribunal’s decision is challenged in a competent court.

When neither party chooses to use the first stage, the parties frequently go straight to the second phase.

The jurisdiction of the arbitral tribunal is typically decided in the second stage of state-to-state dispute arbitration under IIAs. As the jurisdiction of an arbitral tribunal is based on the arbitration agreement, this is based on the provisions of the IIAs.

In addition to determining its subject matter (rationae materiae) and temporal (rationae temporis) jurisdiction, the SSAT must also determine whether a dispute exists and whether the state has given its consent. The “intention of the parties” to arbitrate a specific dispute must also be established.

Arbitration Clause Separability:

The separability doctrine holds that the arbitration agreement can be regarded as an agreement separate from the main contract, preventing a situation where the obligation to arbitrate would not exist if the main contract were found to be invalid.

The principle is reflected in domestic laws and is known as the “who decides” question, holding, in essence, that when parties enter into a main contract and include an arbitration clause, the arbitration agreement is deemed to be part of that main contract.

In state-to-state arbitration, the arbitral tribunal itself has the authority to judge whether the treaty is valid, rather than a court. Although it is a rare occurrence, the award will be automatically void if a compromissory clause of a treaty is found to be invalid.

The arbitration clause for such a determination will be considered independent of the treaty, and an arbitral tribunal is given the authority to decide whether the treaty is valid. The arbitration clause itself will not be rendered invalid by a ruling that the treaty is void.

The contract’s arbitration provision may also be contested under the separability doctrine. It is important to do this in order to ensure that the arbitration clause on which the parties’ consent to the arbitration is based can be carefully examined before the entire dispute is referred to arbitrationtion is based can be carefully examined before the entire dispute is referred to arbitration.

In state-to-state arbitration, the arbitral tribunal is given the authority to consider any challenges to the validity of the clause, whereas in domestic arbitration, this function is typically carried out by a court.

Challenges to the Tribunal’s Jurisdiction

Any international tribunal’s authority to hear a case involving state parties is based on the delegation of authority by “the parties in dispute” and “only to the extent that the states have accepted it.”

The terms of the agreement between the parties to confer the jurisdiction thus limit the tribunal’s authority.

The parties carefully consider the actual scope and the authority that the jurisdictional clauses in the treaties give the tribunal.

In most cases, a challenge to a state-to-state arbitral tribunal’s jurisdiction “must be raised not later than in the statement of defense or, with respect to a counterclaim, in the reply to the counterclaim”

The arbitral tribunal may decide to address the jurisdictional issue as a preliminary question or, in some cases, directly in the final award. It can be argued that a jurisdictional challenge should typically be raised at the first hearing.99 In any case, a challenge to jurisdiction may cause the proceedings to be delayed100, and in those situations where its jurisdiction is contested, the SSAT may need to address the problem.

State Parties’ Mutual Consent to Arbitration

A key factor in determining jurisdiction is the states’ agreement to arbitrate, and no outside party can compel a state to participate in arbitration proceedings. Not only is consent required for establishment, but it is also necessary for the tribunal’s jurisdiction.

States are typically free to decide how to give their consent to arbitration, and no state may be forced to use arbitration or any other dispute resolution method without their consent. The treaty that the parties sign as a commitment to arbitrate or the treaty that creates the arbitrating institution is what governs state-to-state arbitrations the most.

A treaty, protocol, declaration, or other type of agreement wherein the parties agree to submit the disputes before the tribunal without requiring further consent from the other party in the future may be used to express the consent at an earlier stage before the dispute is submitted to the tribunal.

The most common way for states to give their consent for investor-state arbitration is through IIAs. The IIAs typically contain a “compromissory clause” that, as previously stated, “is a provision in a treaty which provides for the settlement by arbitration of all or part of the disputes which may arise regarding the interpretation or application of that treaty.”

This clause pertains to consent for state-to-state arbitration.109 As seen in the USA-Ecuador BIT, some treaties also include additional clauses that state the parties “prior consent to arbitration.”

Explicit consent is also common in many IIAs that Brazil has signed with nations in Latin America, usually through a separate clause that only applies to state-to-state arbitration.

However, there is no explicit advance consent for state-to-state arbitration in the form of a compromissory clause or an explicit consent clause in a few extremely uncommon treaties, such as the Brazil-Malawi ICFA or the new South African investment act.

Before beginning any arbitration proceedings in these situations, it might be necessary to obtain consent through a new agreement.

A state-to-state arbitration may also be started between the parties through an ad hoc agreement reached later on by the parties, which may be in the form of a compromis, even though compromissory clauses may be a common practice in treaties.

Procedures Must Support Arbitration as a Dispute Resolution Method Arbitration as a Dispute Resolution Method Needs to Be Supported by Procedural Provisions.

While compromissory clauses express the parties’ agreement to arbitrate, they frequently contain no information about the specifics of how the arbitration will be conducted, such as the applicable law or the rules of the arbitral tribunal. While some treaties contain in-depth information about the rules of procedure and method, relevant law, and the administrative aspects of the tribunal, others may call for the conclusion of a special agreement (compromis) to address these matters.

The state parties have a great deal of discretion over how the arbitration will be conducted, including choosing the rules and laws that will apply as well as determining the parameters of the award.191 Even then, a compromis or the treaty itself may not address these matters and result in perplexing circumstances, some of which are covered below.

Relevant Law for State to State Arbitration

State-to-state arbitration is typically governed by rules of public international law (lex arbitri193 and lex causae194), and in the absence of an express choice of law, tribunals have used international law as the applicable law.195 State Parties to the Agreement are free to choose the laws that will govern state-to-state arbitration and may do so in place of any applicable customary international law.

Due to the principle of jurisdictional immunity, the generally accepted rule that the law of the seat applies to arbitration is not always true for a state-to-state arbitration, and the IIA may specify the applicable law even when mentioning a seat of jurisdiction. In accordance with their preferences, the parties may also choose to alter the applicable customary international law principles governing state-to-state disputes.

They may also, in exceptional circumstances, give the SSAT express authority to decide a dispute ex aequo et bono199, but a tribunal may not apply this principle without express permission.200

IIAs’ compromissory clauses make references to various sources of relevant law.

For instance, the Australia-Uruguay BIT, 2019, refers to the BIT, other international agreements between the parties, and generally acknowledged principles of international law as the applicable law, whereas the US Model BIT from 2012 refers to “applicable rules of international law.”

The compromissory clause commonly refers to international law in some way as the applicable law, but there may be other sources of law attached to it that the SSAT must also take into account.

These clauses that list “international law” as the applicable law generally imply that the dispute resolution process will be governed by international law and that it must be possible to resolve the dispute in accordance with international law.

In any case, the VCLT’s rules for treaty interpretation and application, which are regarded as embodying primary international law, must be included in and followed by these rules of international law.

Now that international law lacks a legislative body like that of nations, it derives its “legal norms” from a variety of sources, including treaties, judicial rulings, treatises, and academic articles.

As a result, there might be some misunderstanding as to the sources that a tribunal that has been requested to resolve a dispute based on “relevant rules of international law” under Art. 31 (3)(c) VCLT may consider. If further clarification is not provided by the IIA itself, such conflicts may be resolved by the tribunal through a procedural order following consultation with the parties.

As was the case in the IUSCT, where the parties agreed that the legal system of a third country, the Netherlands, governed certain aspects of the arbitration, the parties to a dispute may choose to change the law governing the arbitration and may “waive their sovereignty.” In exceptional circumstances, state-to-state arbitration may also be governed by local or domestic law of a state, but only to the extent that is agreed upon by the parties.

When it comes to the applicable law, agreements sometimes only choose to mention the rules that may govern the arbitration. For guidance on the appropriate law in these situations, the arbitration rules are assessed.

According to the PCA Optional Rules on Arbitration between Two States, for instance, disputes would be resolved in accordance with international law by applying:

(a) International conventions, whether general or specific, establishing rules expressly recognized by the contesting States;

(b) International custom, as proof of a general practice accepted as law; and

(c) The general principles of law recognized by civili

Additionally, PCA Optional Rules make clear that the tribunal must use the legal authorities listed in Art. 38 of the Statute of the ICJ when no special agreement has been made between the parties or when there is no rule that applies to the dispute. The Model Rules also include similar provisions regarding the applicable law to be applied in a dispute in the absence of guidance.214 If both parties agree, tribunals may also rule on a case ex aequo et bono.

However, choosing a set of rules does not guarantee that the applicable law guidance in those rules will be followed; alternatively, separate applicable law guidance may be specified.

Additionally, although choosing a particular forum or institution may indicate a preference for the applicable law, this is not an absolute rule, and the parties may agree to modify the applicable law.

As a result, the parties may in some circumstances decide to grant the tribunal broad discretion over the law, rules, and procedure.

The Iran-US Claims Tribunal (IUSCT), which serves as a state-to-state arbitration tribunal, is one example where no opinion was given regarding the legal framework for the state-to-state interpretative disputes.219 If a dispute relates to a claim for protection under a treaty, the parties to the treaty “may be deemed” to have made an implicit choice for the determination of the dispute under international law.

However, if the parties to an IIA are not recognized as states, as in the case of some Taiwanese BITs, where the parties have reserved the right to decide the terms and conditions later, or have not specified the applicable law, this implicit choice may not be applicable. Before the start of the proceedings, clarification from the parties may be necessary in this case regarding the applicable law.

Applying Rules

The arbitral tribunals must decide disputes in accordance with the applicable arbitration rules, and these rules also have an impact on how the arbitration proceedings are conducted. State-to-state arbitration rules are either (a) established by the tribunal, (b) outlined in the treaty or created through an agreement between the parties, or (c) referred to in pre-existing rules like the Model Rules, UNCITRAL Rules, or PCA Rules.

When a treaty names an institution—such as the SCC, the LCIA, or even an international tribunal like the IUSCT—the state-to-state arbitration proceedings may also be governed by the rules of that institution.

The state parties have the freedom to choose the rules of procedure, and they are free to specify an institutional location for arbitration at their discretion. The tribunal, meanwhile, is free to choose its own procedure and may even set alternative rules.

To fulfill its obligations under the 19581 Convention on the Recognition and Enforcement of Foreign Arbitral Awards (the “New York Convention”), Bangladesh enacted the Arbitration Act in 2001. For both domestic and international arbitration with a seat in Bangladesh, the Act established a single, unified regime.

The Act contains provisions for the enforcement of foreign arbitral awards as well as rules governing the oversight of international arbitration.

The Act is largely based on the UNCITRAL’s (United Nations Commission on International Trade Law) Model Law recommendation for commercial dispute resolution through arbitration and enforcement award, which has been adopted in 80 States and a total of 111 jurisdictions. Bangladesh is unquestionably included by this statute in the current global commercial arbitration trend.

Since the Act was passed in 2001, almost 22 years have elapsed. Bangladesh has yet to be successful in establishing itself as a desirable location for international arbitration. Despite the Act 2001 being based on the Model Law, there are many significant areas where it departs from the Model Law. In many instances, these departures from the Model Law have an impact on Bangladesh’s potential to serve as a preferred venue for international arbitration.

For instance, Bangladesh designated the High Court Division (HCD) of the Supreme Court of Bangladesh to oversee the operations of an arbitration tribunal with a seat in Bangladesh in accordance with the Model Law’s recommendation.

The ability to intervene in the efficient operation of the international arbitral tribunal was expanded by the HCD’s designation, among other things. The current Act broadens the scope of judicial intervention, contrary to the Model Law’s goal of minimizing judicial interference with the operations of the international tribunal.

In addition, Bangladesh’s legal system, which is based on common law and has a written constitution, gives it broad supervisory authority over the operations of any international arbitration with a Bangladeshi seat.

Are you planning to do arbitration or looking for alternative dispute resolution remedies in Bangladesh?

Tahmidur Rahman Remura Wahid TRW is a full-service law firm that has been dealing with arbitration consisting of a wide range of topics at both international and local level. We have barristers that have specialised in international commercial arbitration from the United Kingdom and accredited civil-commercial mediators.

If you require any assistance or consultation, please visit our office or contact us at +8801779127165 or +8801847220062 (WhatsApp) or by email- info@trfirm.com.

GLOBAL OFFICES:

DHAKA: House 410, ROAD 29, Mohakhali DOHS

DUBAI: Rolex Building, L-12 Sheikh Zayed Road

LONDON: 1156, St Giles Avenue, 330 High Holborn, London, WC1V 7QH

Email Addresses:

info@trfirm.com

info@tahmidur.com

info@tahmidurrahman.com

24/7 Contact Numbers, Even During Holidays:

+8801708000660

+8801847220062

+8801708080817