Total Income in Corporate Tax: Scope, Accrual and Source in Corporate Tax

The expressions “scope of total income” and “accrual” (or “accrued”) have special significance within the structure of the Ordinance. Income tax is a geography-based legislation. The taxation power is necessarily limited to subjects within the jurisdiction of the state! These subjects are persons, properties, and businesses? The taxing power of a state cannot reach over into any other jurisdiction to seize upon persons or property for purposes of taxation? Thus, to tax any person under the Ordinance, the income must have nexus to the assessee’s residence or the Bangladeshi source.

It is levied on the profits of companies operating in the Bangladesh (the profits of unincorporated businesses – sole traders and partnerships – are subject to income tax rather than corporation tax). Companies operating in more than one country are, broadly speaking, taxed on the profits that are deemed to have arisen from UK-based assets and production activities.

Features of total income

3.2 Scope ($17(1)): Under $17(1), the extent of total income has a direct nexus with the residence of the assessee. Residence must be determined with reference to the income year and not the assessment year. Two different categories of assessee are captured in $17(1). These are (a) resident assessee in Bangladesh; and (b) non-resident assessee. In the context of companies and other entities captured in (55) of the Ordinance, residence is measured by the control and management test.’ The determination of accrual or receipt of income is a mixed question of law and fact for the DCT or the tribunal to decide. But the determination of the DCT or the tribunal on the question of fact must not be perverse or unsupported by evidence. Once facts are ascertained, the issue of whether or not certain income accrues to the assessee is a question of law?

Resident assessee in Bangladesh (517(1)(a)): Resident assessees are charged on (a) income received or deemed to be received in Bangladesh in the income year without any regard to the date or place of such income’s accrual (§17(a)(i)); (b) income which accrues or arises, or is deemed to accrue or arise in Bangladesh during the income year without any regard to the date or place of its receipt ($17(a) (ii)); or (c) income which accrues or arises outside Bangladesh during the income year without any regard to whether or not such income is received or brought into Bangladesh.

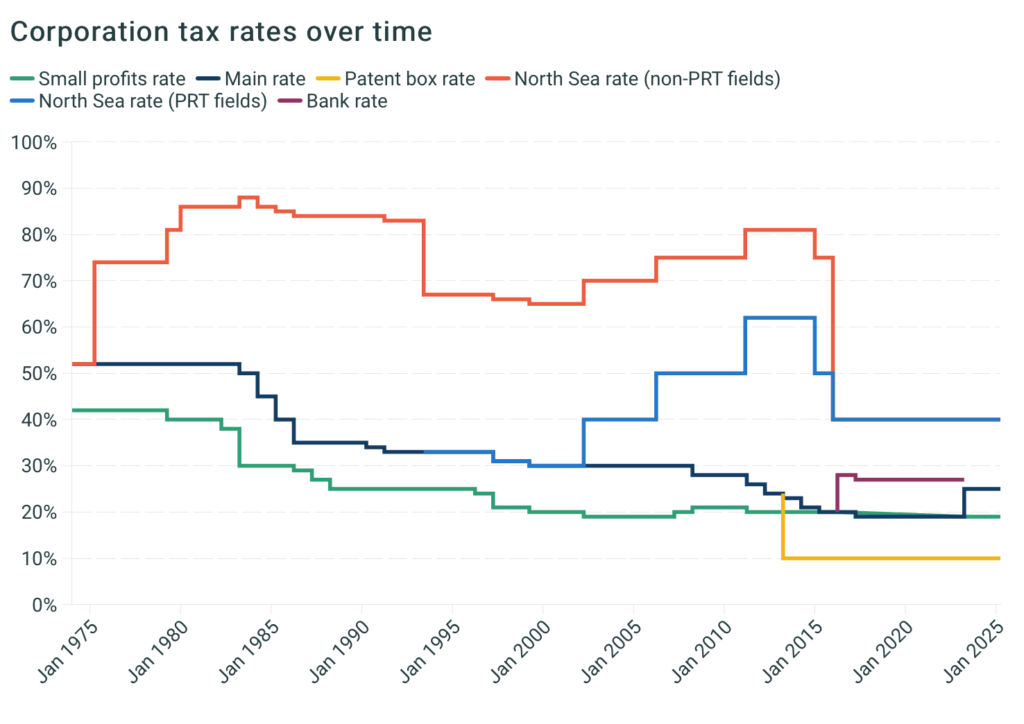

Taxable profits

Profit is broadly defined as revenue minus costs.

Corporation tax is levied on income from trading (the sale of goods and services) and investments, less day-to-day expenses (known as ‘current’ or’revenue’ expenditure, which includes wages, raw materials, and interest payments on borrowing) and various other deductions, most notably allowances for investment costs. It is also levied on capital gains (‘chargeable’), which are the profits made by selling an asset for more than it cost. If a corporation loses money because its costs exceed its revenue, it might, subject to certain conditions, offset the loss with profits from previous years.

While most current expenses are deductible, research and development (R&D) tax breaks allow businesses to deduct more than 100% of eligible current expenses for R&D. R&D tax breaks are more substantial for small and medium-sized businesses than huge corporations.

Non-resident assessee in Bangladesh:

Non- resident assessees are charged on (a) income received or deemed to be received in Bangladesh in the income year without any regard to the date or place of such incomes accrual ($17(b)(i)); or (b) income which accrues or arises, or is deemed to accrue or arise in Bangladesh during the income year without any regard to the date or place of its receipt (517(b)(ii)).

Distinction between $17(a) and $17(b):

The distinction between $17(a) and $17(b) is that all assessees, whether resident or not, are chargeable to tax for income received, accruing or arising, deemed to be received or to accrue or arise, in Bangladesh; but in case of a resident assessee, tax is also charged on income, which accrues or arises or is received outside Bangladesh. Meaning of “Subject to the provisions of this Ordinance”: The scope of total income in $17 is “subject to the provisions of this Ordinance”. This means that other provisions of the Ordinance may operate to save income from the net of taxation which is otherwise within the scope of Section 17. For example, any gazette notification under $144 of the Ordinance to implement a double taxation avoidance agreement would automatically override the charging section (§1611) and the scope of total income (§17).12

Meaning of “from whatever source derived” ($17(1)(a) and (517(1)(6)): The word “source” is not a legal concept but must be understood from the standpoint of a practical man who would regard something as a real source of income.!3 A legislation’* or a decree of the court’s may constitute a source of income. The expression “from whatever source derived” is inserted to make it clear that the source is irrelevant for determining scope of income under $17,163.8 Meaning of “received or deemed to be received”. These expressions capture all income received or deemed to be received in Bangladesh by the assessee regardless of whether or not he is a resident or non-resident. Under these expressions, liability to tax depends on the locality of the receipt and if the receipt is in Bangladesh, the question of the place of accrual does not arise at all.

Meaning of “accrues or arises, or is deemed to accrue or arise:

The requirement of “receipt” is not the only method of taxability under the Ordinance. $17 expressly brings to charge income which is not only received but income which has accrued or arisen.” Also, income may be brought to charge under $17 if it is deemed to have accrued or arisen and may not have accrued or arisen in actuality?® It is important to note that the requirement of receipt is not needed at all for at least two heads of income. $21 states that salary will be taxed if it is due from an employer, regardless of whether it has been paid or not.” In addition, $22 states that interest on securities will be classified as income if it is receivable by the assessee?? However, sections like $19(7) in the Ordinance charge tax solely on receipt basis? The effect of the word “accrue or arise” is that an assessee might be taxed on income which has accrued or arisen but not actually or constructively received by the assessee.24 If the point of sale or transaction of a non-resident does not occur in Bangladesh, then any income arising from such sale or transaction will not be regarded as accrued in Bangladesh even though the goods that are purchased from such sale or transaction are brought to Bangladesh for some works When one refers to the right of the assessee to receive an amount, it necessarily means a right enforceable under the law26 and to which the assessee is entitled? The financial treatment of contractual payment is also recognised on receipts basis and accrual basis under IFRS 15.28 Under the receipts basis, IFRS S 15 stipulates that Concept of Total Income: Scope, Accrual and Source 45

when an entity receives a consideration from a customer, the entity shall recognise the consideration received as revenue only when (a) the entity has no remaining obligations to transfer goods or services to the customer and all, or substantially all, of the consideration promised by the customer has been received by the entity and is non-refundable; or (b) the contract has been terminated and the consideration received from the customer is non-refundable.29 Conversely, under the accrual method, when (or as) a performance obligation under a contract is satisfied, a supplier of goods or services shall recognise as revenue the amount of the transaction price that is allocated to that performance obligation. Thus, in recognising income on an accrual basis, the point of derivation of such income occurs when a “recoverable debt” is created under the contract, which means the point of time at which an assessee is legally entitled to anascertainable amount as the result of having performed an agreed task.

The payment of retention money under a contract can only be forfeited if there is a breach of contract and the right to receive the retention money accrues only after a certain contingency occurs, and therefore, until such contingency occurs, the retention money would not become the income of the assessee in the year in which the amount is retained. If a debt is payable in the future and not in the income year, then it might be difficult to hold that the cash amount of the debt has accrued to the assessee in the income year because he has not become entitled to a right to claim payment of the debt in the income year but he has acquired a right to claim payment of the debt in future. This right has vested in him, has accrued to him in the income year and it is a valuable right which he could turn into money if he wished to do so, and the value of this right shall be included in the assessee’s total income for taxation purposes. In other words, the assessee may have a recoverable debt as accrued income even though, at the time, he cannot legally enforce recovery of the debt. Thus, income may accrue at a point of time prior to its quantification or computation which is not a condition precedent to accrual 353.11 Distinction between “accrues” and “arises”: There is not much distinction between the words “accrues” and “arises” when it comes to the locality of income. But there is a distinction between these two words when deciding the date of income.

This can be illustrated by an example. Under $35(1), business income (under §28) and income from other sources (under §33) shall be computed in accordance with the accounting method regularly employed by the assessee. Under §17, business income “accrues” when it first comes into existence or the right to receive such income first comes into existence and yet, business income will “arise” when the accounting method adopted by the assessee under $35 shows it in the shape of profits or gains.? This will commonly happen when the assessee maintains a mercantile or hybrid system of accounting. The date of taxability of income under the mercantile or hybrid system of accounting as employed by the assessee is the date when appropriate entries are made or should be made in the books of accounts. it wereo) as income accruing or received. An example of this type of deeming provision is $48(2)*, where income may in reality accrue but may not be actually received by the assessee and yet the Ordinance deems it to be received.

(b) The income accrues or is received not in Bangladesh but abroad and the Ordinance requires it to be treated as if it accrued or were received in Bangladesh. In this sense, the legal fiction only fixes the place where the income is deemed as having accrued or arisen. 42

(c) The income may be deemed to be the income of the person sought to be taxed though in reality it is the income of someone else. 43 In other words, the Ordinance taxes the statutory owner of the income as opposed to the real owner of such income.

(d) The income may be deemed to be the income of the income year when in reality it is the income of a different year.* To put it another way, the Ordinance creates an artificial year of taxability without any regard to the actual year of accrual or receipt of the income.

3.13 Meaning of “accrues or arises outside Bangladesh” ($17(1) (a)(ir)): Under this sub-section, in case of residents, income accruing outside Bangladesh is taxed exactly like income accruing in Bangladesh. It is important to note that under $17(1)(a)(iii), for charging of tax, income must actually accrue and cannot be deemed to have accrued outside Bangladesh. In other words, any income in the hands of the assessee in a foreign country must be computed under $17(1)(a)(iji) on a net basis and any tax deducted from the income by the foreign tax authority shall not be included in the total income of the assessee in Bangladesh.

But if an assessee is assessed on income that accrued abroad but cannot be remitted to Bangladesh due to prohibitory laws of the foreign country, then the assessee cannot be treated as in default in respect of that part of the tax which is due from the income that cannot be brought to Bangladesh as a result of the prohibition or restriction in the foreign country.173.14 Income cannot be taxed twice (517(2)): If income is taxed under one of the sub-sections on the basis of accrual or deemed accrual, it cannot be taxed again under another sub-section either in the same year or in a different year on the basis of receipt.

Tax on retained earnings, reserve surplus:

Scope: Under $16G of the Ordinance, notwithstanding anything contained in the Ordinance or any other law for the time being in force, if in an income year, the total amount transferred to retained earnings or any fund, reserve or surplus, called by whatever name, by a company registered under the Companies Act 1994, and listed on any stock exchange, exceeds 70% of the net income after tax, then 10% tax shall be payable on the total amount so transferred in that income year. This appears to be a deterrent provision to compel listed companies to pay out at least 30% dividend to its shareholders. 49 However, the words “retained earnings”, “fund”, “reserve” and “surplus” are not defined in the Ordinance. Therefore, there is room for confusion and absurd results in the absence of clear definitions of these words.

For example, the word “surplus” has multiple meanings in corporate finance parlance- it could mean “paid-in surplus”, where the share is issued at a price above par (also called “shares issued at a premium”5), or “earned surplus” (also known as “retained earnings”), where it is derived wholly from undistributed profits; or it may, among other things, represent the increase in valuation of land or other assets made upon a revaluation of the company’s fixed property.

In contrast, despite the characterisation of share premium amounts (the “paid-in surplus”) as “surplus”, the share premium amount received on the issue of shares has to be included in the paid up capital of the company under $57 of the Companies Act 199452 In other words, amounts in the share premium account are not accumulated profits (or “earned surplus”) because $57 of the Companies Act 1994 puts a statutory bar on share premium accounts being used for distribution of dividend. Again, there are instances where the words “earned surplus” and “reserve” have been given the same meaning. Thus, although a share premium account falls within the generic meaning of the word “surplus” from which there may be distribution of dividend to shareholders, it is actually not a “surplus” in that sense but a part of the paid up capital of a company. It is submitted that these types of confusion will continue to occur unless the words “retained earnings”, “fund”, “reserve”, and “surplus” are defined in the Ordinance.

3.16 Also, the non-obstante clause in §16G has the potential to pose problems for banking companies or listed companies that are required to maintain reserves as per the direction of the Bangladesh Bank or Bangladesh Securities and Exchange Commission. Generally, reserves or provisions maintained by banking companies or listed companies under the direction of the Bangladesh Bank or Bangladesh Securities and Exchange Commission are not calculated as part of the income of such companies because such reserves or provisions are being created and maintained under compulsion of the regulators (the Bangladesh Bank or Bangladesh Securities and Exchange Commission). It is submitted that there should be clarity and carve-out in §16G of the Ordinance with respect to tax exemption of reserves or provisions maintained by companies under the direction of the regulators (like the Bangladesh Bank or the Bangladesh Securities and Exchange Commission).

Scope:

The basic conceptof $18 captures the principle of source- based taxation in Bangladesh. Various categories of income under $18 deal with deemed accrual of income in Bangladesh, which apply to both residents and non-residents. Once income is chargeable to tax under $17, the provisions of $18 shall be applicable. Once $18 becomes applicable, the nature of the income shall be determined in accordance with the various sub-sections of $18. When it comes to a non-resident, the provisions of $18 must always be read keeping in mind the existence of any Double Taxation Avoidance Agreement (DTAA)s that the non-resident’s country may have with Bangladesh under $144 of the Ordinance. 3.18 The concept of source: The Ordinance does not define the word “source”. Also, no court has managed to provide an all embracing and authoritative definition. As a result, the exercise to determine a particular source of income becomes a fact intensive inquiry by the court. The difficulty of determining a source of income is succinctly summarised by the South African Appellate Division in the case of CIR v. Lever Bros & Unilever in the following words:

“The work… may be a business which he carries on, or an enterprise which he undertakes, or an activity in which he engages and it may take the form of personal exertion, mental or physical, or it may take the form of employment of capital either by using it to earn income or by letting its use to someone else. Often the work is some combination of these … Turning now to the problem of locating a source of income, it is obvious that a taxpayer’s activities, which are the originating cause of a particular receipt, need not all occur in the same place and may even occur in different countries, and consequently, after the activities which are the source of the particular “gross income” have been identified the problem of locating them may present considerable dificulties, and it may be necessary to come to the

conclusion that the “source” of a particular receipt is located

partly in one country and partly in another. … Such a state of affairs may lead to the conclusion that the whole of a receipt, or part of it, or none of it is taxable as income from a source within the Union, according to the particular circumstances of the case,

but I am not aware of any decision which has laid down clearly what would be the governing consideration in such a case.”61

The problem of “locating the source” is closely connected with the territorial nexus of the income. Also, the determination of the source of income must be assessed from the point of view of a practical person operating within the realities of any given state of affairs. In Nathan v. FCT, the High Court of Australia formulated the concept of source from the viewpoint of a practical man in the following words:

“The legislature using the word “source” meant, not a legal concept, but something which a practical man would regard as a real source of income. Legal concepts must, of course, enter into the question when we have to consider to whom a given source belongs. But the ascertainment of the actual source of the given income is a practical, hard matter of fact.”63

The expression “practical, hard matter of fact” in Nathan

v. FCT& was further explored in the case of Thorpe Nominees Pty Limited v. FCT&S from the point of view of the business realities of a given transaction in the following words:

“The frequently cited passage from the joint judgment in Nathan’s case that the actual source of a given income is a practical, hard matter of fact, if analyzed too closely, may raise a question in some minds about what it really means. For this reason some may question its usefulness as a guide in the inquiry which has to be made, but, in my respectful opinion, the judges in Nathan’s case said what they did to emphasize the factual nature of the inquiry and that the touchstone was practical reality. That is the theme which runs through judgments in later cases. Obviously the word “hard” was not used in the sense of difficult, but as an indication to a person concerned with making the inquiry that it was necessary to be down-to-earth, practical and hard- headed about the task in hand.

Practical reality is not a test so much as an attitude of mind in which the Court should approach the task of judgment. Reality,

like beauty, is often in the eye of the beholder. (Cf. the comments

made by J.D. Jackson in an article in 51 Mod LR 549 at 557 et seq. What the cases require is that the truth of the matter be sought with an eye focused on practical business affairs, rather than on nice distinctions of the law. For the word “source”, in this context, has no precise or technical reference. It expresses only a general conception of origin, leading the mind broadly, by analogy. The true meaning of the word evokes springs in grottos at Delphi, sooner than the incidence of taxes. So the exactness which the lawyer is prone to seek must be consciously set aside; indeed, with respect to a choice between various contributing factors, it cannot be attained. The substance of the matter, metaphorically conveyed when we speak of the source of income, is a large view of the origin of the income — where it came from — as a businessman would perceive it.”

However, the rise of information technology has challenged the interrelation between location of the source, the practical realities of the matter, and territorial nexus, which is discussed in more detail later in this Chapter.

Source of income-Salaries (518(1)): Under $18(1), an artificial place of accrual for salary income is stipulated. The words “wherever paid” signify that the place of receipt or actual accrual of salary income is irrelevant if the salary is “earned” in Bangladesh (under $18(1)(a))69, which means the assessee providing his service under an employment contract in Bangladesh?°

Conversely, under $18(1)(b), it appears that taxability of salary in Bangladesh depends on payment of salary by the Government in Bangladesh. The sub-section is unclear in the case where payment of salary is made by the Government outside Bangladesh for services rendered abroad. It is submitted that the words “wherever paid” in the starting line of $18(1) have become diluted with the words “paid … in Bangladesh” appearing in $18(1)(b). It could be argued that the words “paid … in Bangladesh” indicate that if Government employees are sent abroad and are paid salaries abroad for services that are rendered abroad, then such payment shall not be deemed to accrue or arise in Bangladesh under $18(1)(b).”

Source of income-Expanding the territorial nexus (§18(2)):

Under $18(2) of the Ordinance, any income is deemed to accrue or arise in Bangladesh, whether directly or indirectly, through or from: (a) any permanent establishment in Bangladesh; or (b) any property, asset, right or other source of income, including intangible property in Bangladesh; or (c) the transfer of any assets situated in Bangladesh; or (d) the sale of any goods or services by any electronic means to purchasers in Bangladesh; or (e) any intangible property used in Bangladesh. The Finance Act 2018 amended $18(2). The previous version of 518(2) had a more restrictive application of the source principle?” Importantly, the words “business connection” appearing The unamended $18(2) (pre-Finance Act 2018 version) stated as follows-

Income deemed to accrue or arise in Bangladesh. The following income shall be deemed to accrue or arise in Bangladesh, namely:-

(2) any income accruing or arising, whether directly or indirectly, through or from- (a) any business connection in Bangladesh; (b) any property, assel, right or other source of income in Bangladesh; or

in the unamended $18(2)(a) (pre-Finance Act 2018 version) have been removed altogether and the words “permanent establishment” have been introduced in §18(2)(a) by the Finance Act 2018. This change shows that the Bangladesh Government is inclined to make the source principle more aligned with the concepts of international taxation and DTAAs.3

Source of income-Permanent establishment:

The amended §18(2)(a) (under the Finance Act 2018) introduced the concept of “permanent establishment” (PE) in the Ordinance. The objective of inclusion of permanent establishment in §18(2)(a) is to expand the ambit of taxation of non-residents?* The Finance Act 2018 also defines the words “permanent establishment” by inserting $2(44A) in the Ordinance. The definition of “permanent establishment” in $2(44A) is inspired by the definition of “permanent establishment” in Article 5(1) of the Model Tax Convention on Income and on Capital prepared by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). The OECD Model Tax Convention generally forms the basis of Double Taxation Avoidance Agreements (DTAAs) signed by Bangladesh with other countries. But there are crucial differences between the two definitions of “permanent establishment” appearing in Article 5(1) of the OECD Model Tax Convention and $2(44A) of the Ordinance, which are as follows:

(a) Article 5(1) of the OECD Model Tax Convention stipulates “a fixed place of business” for a PE? But $2(44A) requires “a place or activity” for there to be a PE. It appears that $2(44A) has a wider coverage than the OECD Model’s definition of “permanent establishment”.

(c) transfer of capital assets in Bangladesh:

For example, under the OECD Commentary, for determining PE, a “place of business” must be tangible and cannot include an internet website. But under $2(44A) of the Ordinance, the words “a place or activity” may include a moving vessel” or a residential premises.78 (b) Article 5 of the OECD Model Tax Convention has a specific time limit for a building site or construction or installation project to be regarded as a PE?” But $2(44A) of the Ordinance has no such carve-out for a building site or construction or installation project.80

(c) Under Article 5 of the OECD Model Tax Convention,

an entity or person performing supervisory activity will not constitute a PE.81 But $2(44A) of the Ordinance captures supervisory activities within the ambit of PE.82 (d) Article 5 of the OECD Model Tax Convention has

specific exclusions from the ambit of PE for certain types of business activities.83 For example, under the OECD Model Tax Convention, activities like (i) use of facilities solely for the purpose of storage, display or delivery of goods; (ii) maintenance of a stock of goods foi the purpose of storage, display or delivery; (iii) maintenance of a stock of goods for the purpose of processing by another enterprise; or (iv) maintaining a fixed place of business solely for the purpose of purchasing goods or merchandise or of collecting information are not deemed as PE.8 But S2(44A) of the Ordinance has not provided such carve-out for any type of activities. On the contrary, $2(44A) captures a Bangladeshi “associated entity or person” that is “commercially dependent” on a non-resident person, as a PE if that associated entity or person carries out any activity in Bangladesh in connection with any sale made by such non-resident person in Bangladesh.®s The NBR has explained that any entity or person undertaking “any activity” in Bangladesh that is related

or connected with the sale of any goods or products of the non-resident in Bangladesh will be regarded as a PE of that non-resident.86

The definitional expansion of the words “permanent establishment” under $2(44A) of the Ordinance will have broader tax impact on foreign entities whose country of incorporation or registration does not have a DTAA with Bangladesh. The definition of PE under S2(44A) has captured all the supportive services in Bangladesh which are otherwise immune from local taxation® under Article 5 of the OECD Model Tax Convention. The definition of “permanent establishment” under the OECD Model Tax Convention

contemplates a virtual projection of the foreign enterprise into the soil

of another country and requires substantial existence of an enduring nature of such foreign enterprise in another country.®* But $2(44A) of the Ordinance does not require substantial engagement by or virtual projection of the foreign enterprise in Bangladesh for there to be a PE.

However, it seems that S2(44A) carves out two exceptions. First, an associated entity or person must be “commercially dependent” for the purpose of PE. In other words, for there to be a PE under $2(44A), the Bangladeshi establishment must be at the disposal of the foreign enterprise, and it must have some right or control over the place in Bangladesh before it could be labelled as a PE.” By this logic, a subsidiary company in Bangladesh will be regarded as a PE of the foreign parent company if that subsidiary is controlled by the foreign parent and has no independent activity.’ Secondly, the commercially dependent person or entity must carry out an activity in Bangladesh “in connection with any sale made in Bangladesh by the non-resident person”.

In other words, if a commercially dependent person or entity does something “in connection” with any sale made outside Bangladesh by the non-resident person, then such commercially dependent person or entity will not be regarded as a PE under S2(44A) (xii) of the Ordinance. For example, if a Bangladeshi company, which is commercially dependent on a foreign corporation, purchases raw materials in Bangladesh, which are sent to the country where the foreign company is resident, for the purpose of manufacturing and sale of any finished goods in that country using the raw materials that are purchased in Bangladesh, then the Bangladeshi company will not be regarded as a PE under 52(44A)(xii) of the Ordinance because the sale by the foreign company does not take place in Bangladesh? This conclusion is also in line with Article 5(4)(d) of the OECD Model Tax

• §2(44A)(xii) of the Ordinance

∞ See Macneill & Barry v. Commissioner of Income Tax 21 DLR (SC) 200 (assessee- company based out of Pakistan had full control of the business operation of managed company in Pakistan. Commission earned by the assessee-company from such management in Pakistan was taxable in Pakistan). Also see Jardine Henderson v. Commissioner of Income Tax 28 DLR (AD) 129 at para. 14; Octavius Steel Co v. Commissioner of Income Tax 12 DLR (SC)

Convention’ under which maintenance of a fixed place of business solely for the purchase of goods is not PE.

3.28 Impactof Covid-19 on the status of PE: The ongoing coronavirus (Covid-19) pandemic raises important questions regarding the issue of PE. Specifically, the anxiety stems from the concern that employees of a foreign company dislocated to jurisdictions (for example, to Bangladesh) other than the one in which they regularly work, and working from their homes during the Covid-19 pandemic, could create a PE in those jurisdictions, which may trigger for those foreign companies new filing requirements and tax obligations under the jurisdiction in which its employees are stranded due to Covid- 19.4 The same concern relates to a potential change in the “place of effective management” of a company as a result of a relocation, or inability to travel, of board members or other senior executives.’ The concern is that such a change may result in a change in a company’s residence under relevant domestic laws and affect the jurisdiction where a company is regarded as a resident for tax treaty purposes.*

The starting point for this problem is to see the language employed to determine residence for individuals under the Ordinance. Under §2(55)(a) of the Ordinance, there are two alternative day-based tests for residence for individuals. Under S2(55)(a)(i), if an individual stays in Bangladesh for at least 182 days cumulatively in the course of the relevant income year, then he will be regarded as a resident. Under $2(55)(a)(ii), there are two conditions-(x) remaining in Bangladesh in the income year for a period or periods aggregating to at least 90 days; and (y) the total stay must be at least 365 days in Bangladesh in the course of 4 years preceding the income year. The expression “four years preceding” means the period of 4 years of 12 calendar months each which is immediately preceding the commencement of the relevant income year, and does not mean the period of 4 calendar years ending on 31 December immediately preceding the commencement of the relevant income year?®

3.30 For an individual taxpayer, the treaty language employs two tests of residency: (a) the “residence test” and (b) the “domicile test”. For companies, it employs the place of management test.” For residency of individual taxpayers, under Article 4(1) of the OECD Model Tax Convention’®®, , the term “resident of a Contracting State” means any person who, under the laws of that State, is liable to tax therein by reason of his domicile, residence, place of management or any other criterion of a similar nature.

The same language is captured in, for example, the DTAA between Bangladesh and Bahrain, 101 However, it is curious to note that the tests of residency under $2(55) (a) of the Ordinance and the DTAA between Bangladesh and Bahrain have no similarity. Article 4(1)(b) of the DTAA between Bangladesh and Bahrain states that the expression “resident of Bangladesh” means any person who, under the laws of Bangladesh, is liable to tax therein by reason of his domicile, residence, and place of management or any other criterion of a similar nature.

Article 4(1)(b) of the DTAA between Bangladesh and Bahrain does not mention any day-based residency test. In this regard, the OECD acknowledges that in addition to the “residence test” and “domicile test”, the test of residency also covers persons who stay continually, or maybe only for a certain period, in the territory of a State.102 Thus, the OECD acknowledges a day-based test that a State may adopt to determine residency for tax purposes, and in that sense the expression “criterion of a similar nature” as stipulated in Article 4(1)(b) of the DTAA between Bangladesh and Bahrain may include a day-based test under $2(55)(a) of the Ordinance.

3.31 In the “residency test”, the common law principles dictate that the following factors are relevant to the concept of residency:

(a) a person resides where he lives and dwells permanently or for a considerable period of time, being the place where he makes his home; (b) a person’s intention to make a particular place “home” either permanently or temporarily is an elemental consideration in the identification of where he resides; (c) once a person has a home in a particular place he does not necessarily cease to be a resident there merely because he is physically absent. The determinative question is whether he has retained a continuity of association with the place, together with an intention to return to that place which he considers remains his “home”; (d) determining a person’s “continuity of association” in a particular place requires a consideration of all the relevant circumstances, including whether he has retained in that locale a physical home to which he can return, a family unit, possessions, and relationships with people and institutions; (e) the person’s own evidence as to his previously held intention is admissible as are any contemporaneous statements of intention, however the objective manifestations of his state of mind at the time are usually more reliable; and (f) the facts and circumstances surrounding a person’s mode of living will be an indicator of his presence in or continued association with a particular place and the intention accompanying that presence or continued association. 103 It is submitted that the element of “intention” being a determining factor for ascertaining tax residency is equally applicable in a day- based test of residency under 52(55)(a) of the Ordinance. The starting line of $2(55)(a) uses the words “has been in Bangladesh” to determine actual presence in Bangladesh for a person to be regarded as a resident. The words “has been in Bangladesh” must necessarily mean that the person must be voluntarily in Bangladesh for the day- based test to trigger under S2(55)(a). In other words, the option to be in Bangladesh, or the period for which a person desires to be here is a matter of his discretion. Therefore, it follows that if a person’s presence in Bangladesh is against his will or without his consent and if the person was compelled to remain in Bangladesh by external circumstances beyond the individual’s control, then such presence should not ordinarily be counted towards calculating the days under

‘ Addy v. Commissioner of Taxation (2019) FCA 1768 at para. 76 * CIT v. Suresh Nanda 375 ITR 172 (Del)

Concept of Total Income: Scope, Accrual and Source 61

$2(55)(a), and he cannot be treated as a resident for the purpose of $2(55)(a),” It is submitted that to read involuntary presence in Bangladesh as part of the day-based test under §2(55)(a) would result in absurdity and an inequitable situation, which must be avoided even in interpreting a taxing statute. 06

3.32 It is submitted that the current situation with the Covid-19 pandemic and the issue of tax residency in the context of PE should be considered in light of the above principles. A person may reside in a particular place only because he has to do his work at or near a place. There are two aspects of “voluntariness” in this situation-one is the voluntary choice made by that person to agree to an employment at a designated place, and the other is the voluntary nature of mobility to and from that place by that person at a given point in time. If voluntary choice is to be regarded as an important element in determining residence, then both these elements must be taken into account to determine whether there was any “voluntariness” for a person to remain at a place during the Covid-19 pandemic.

If the facts show that the residence of a person in Bangladesh is required by the exigencies of his duties, then such a person shall be regarded as a resident under the day-based test of $2(55)(a) regardless of whether or not the Covid-19 pandemic exists. However, if it could be shown that the individual’s presence in Bangladesh has nothing to do with his employment and such presence in Bangladesh is forced upon that individual due to the Covid-19 pandemic, then such presence cannot be regarded as the exigencies of his duties, and consequently, the period of such presence should be outside the calculated period under the day-based test of $2(55)(a).

3.33 Indeed, the OECD has come to the same conclusion while dealing with PE and the Covid-19 pandemic. According to the OECD, for employees of a foreign company deployed in another jurisdiction, the exceptional and temporary change of the location where employees exercise their employment because of the Covid-19 pandemic, such as working from home, should not create a new PE for the foreign employer. 08 Similarly, the temporary conclusion of contracts in the home of employees or agents because of the Covid-19 pandemic should not create PE for the businesses, ” Also, with respect to a company’s effective control and management, it is unlikely that the Covid-19 situation will create any changes to an entity’s residence status under a tax treaty, and a temporary change in location of board members or other senior executives is an extraordinary and temporary situation due to the Covid-19 pandemic and such change of location should not trigger a change in treaty residence!° It is hoped that the NBR will take these points into consideration while dealing with the Covid-19 pandemic and foreign personnel who are stranded in Bangladesh.

The burden of proving that the foreign entity has a PE in Bangladesh is initially on the NBR.”!

Source of income-property, asset, right or other source including intangible property (§18(2)(b)): Under the unamended §18(2)(b) (pre-2018 Finance Act version), there was no clarificatory language like “including intangible property” while dealing with the word “property”. This caused taxation uncertainty because the Privy Council held that intangible property like a debt or other choses in action was not “property” under the unamended $18(2)(b) (pre- 2018 Finance Act version) and it meant something tangible.!12 The amended $18(2)(b) (as per the Finance Act 2018) has clarified this uncertainty and now any direct or indirect income through or from any property, including intangible property in Bangladesh shall be deemed to accrue or arise in Bangladesh. Any dividend paid by a Bangladeshi company which accrues abroad (meaning they are declared and made payable abroad) may nevertheless be deemed to accrue in Bangladesh under $18(2)(b) because the “source” of the OECD Updated guidance on tax treaties and the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, dated 21.01.2021, at para.

Concept of Total Income:

Scope, Accrual and Source 63 dividend (i.e. the income) is the shareholding in the company, which is in Bangladesh.113 This principle is now captured in Explanation (a) to §18(2) which stipulates that the shares of any company which is a resident in Bangladesh shall be deemed to be property in Bangladesh. The NBR has clarified that the identity of the shareholder is irrelevant for the purpose of Explanation (a) to §18(2).”

With respect to intangible property, Explanation (b) to §18(2) stipulates that intangible property shall be deemed to be property in Bangladesh if it is (i) registered in Bangladesh; or ii) owned by a person that is not a resident of Bangladesh but has a permanent establishment in Bangladesh to which the intangible property is attributed. The word “registered” as used in Explanation (b)(i) to $18(2) should be read with reference to $3(45) of the General Clauses Act 1897 when used with reference to a document, and it shall mean registered under the law for the time being in force for the registration of documents. But this line of reading raises a question-what will happen to documents that “create” or “generate” intangible properties but do not require registration under the laws of Bangladesh?

Not all documents are compulsorily registrable in Bangladesh.”s Thus, for example, intangible property like cryptocurrency 16 or actionable claim 17 will be deemed to be property in Bangladesh if it is generated and created in Bangladesh or in case of a debt, the intangible property (that is, the right to such debt) will be deemed to be in Bangladesh if the debtor is or the loan agreement is executed in Bangladesh.!18 However, the creation, generation, assignment or transfer of these types of intangible properties may not require any “registration” in Bangladesh.!’ In such a case, it is unclear whether non-registration of these types of intangible properties would be outside the deeming provision of Explanation (b)(i) to 518(2). It is submitted that the word “registered” appearing in Explanation (b)(i) to $18(2) should be changed to the word “created” to avoid this confusion.

Explanation (b)(is) to §18(2) deems an intangible property to be located in Bangladesh ifit is owned by a person that is not a resident of Bangladesh but has a permanent establishment in Bangladesh 1o which the intangible property is attributed. The word “attributed” is not defined in the Ordinance. It means “caused by or resulting from” or connection to the principal source!» Thus, any intangible property stemming from a non-resident’s PE in Bangladesh shall be deemed to be in Bangladesh.

Source of income-transfer of any asset situated in Bangladesh:

Any income arising from transfer of asset (movable or immovable) situated in Bangladesh is deemed to have accrued or arisen in Bangladesh regardless of the location of execution of the transfer agreement under which the transfer is made or payment location from where the transfer price is paid. 21 If shares of a Bangladeshi company is transferred between two non-residents, income will accrue or arise in Bangladesh because the asset (that is, shares) is situated in Bangladesh.

What happens if two non-residents transfer shares of a foreign company that has shares in a Bangladeshi company?

Logically, the answer will be Bangladesh would have no taxing jurisdiction over this transaction. But the Finance Act 2018 introduced Explanation (c) 10 $18(2) of the Ordinance to capture an offshore share transaction involving foreign companies by stipulating that the transfer of any share in a non-resident company shall be deemed to be the transfer of an asset situated in Bangladesh to the extent that the value of the of an actionable claim (with or without consideration) shall be effected only by the execution of an instrument in wring signed by the transferor or his duly authorised agent, and shall be complete and efectual upon the execution of such instrument share transferred is directly or indirectly attributable to the value of any assets in Bangladesh.

The word “attributable” is not defined in the Ordinance. It means connection to the principal source. 23 Thus, under Explanation (c) to $18(2), a share transfer of foreign companies outside Bangladesh would result in capital gain in Bangladesh if any gain from such share transfer has any direct or indirect connection to any assets in Bangladesh. In other words, Explanation (c) to §18(2) creates a legal fiction and deems such shares, albeit in a foreign company, to be situated in Bangladesh. It is submitted that this is a tremendously odd and disturbing treatment of settled principles of source taxation. It is well settled that shares in a company have a situs at the domicile of the company!25 It is equally settled that the situs of an intangible asset will be the situs of the owner of such asset. 126 The rationale for the fiction of situs was explained by the US Supreme Court in the following words: “.. the interest represented by the shares is held by the Company for the benefit of the true owner. As the habitation or domicil of the Company is and must be in the State that created it, the property represented by its certificates of stock may be deemed to be held by the Company within the State whose creature it is, whenever it is sought by suit to determine who is its real owner.”

Explanation (c) to §18(2) has completely discarded the above settled principles of situs and stipulated a diametrically opposite proposition. Under Explanation (c) to §18(2) of the Ordinance, the NBR will be able to tax transactions involving, for example, transfer of an Australian company’s shares between two Australians if the shares in the Australian company derive their values from assets held Corporate Tax Law & Practice by the Australian company’s Bangladesh subsidiary. This stance goes completely against Bangladesh’s position before the international legal regime. For example, under Article 13(4) of Bangladesh-UK Double Taxation Avoidance Agreement (DTAA), capital gains arising out of transfer of shares shall be taxed by the country of residence of the transferor (or alienator).128 But the same treatment is not provided to a non-resident whose country may not enjoy an executed

Double Taxation Avoidance Agreement (DTAA) with Bangladesh:

It is submitted that Explanation (c) to §18(2) will cause a serious dent to Bangladesh’s bid to attract more foreign investment and steps should be taken to omit or delete this provision from the Ordinance.

Source of income-sale of goods or services by electronic means under (§18(2)(d)): This sub-section intends to capture electronic commerce (or popularly known as e-commerce) transactions in Bangladesh. The words “electronic means” are not defined in the Ordinance. It has been described as “the sale or purchase of goods or services, conducted over computer networks by methods specifically designed for the purpose of receiving or placing of orders” 129 By inserting §18(2)(d) through the Finance Act 2018, the Bangladesh tax regime introduced tools to tax e-commerce activities, which were posing challenges to cross-border and international taxation methods. In

this regard, the OECD BEPS Project130 noted that the “spread of the digital economy” posed “challenges for international taxation”131 Action 1 of the OECD BEPS Project deals with tax challenges of the digital economy. In its 2015 Final Report, the causal link between non-resident companies and source taxation was discussed in the following words:

Serco BPO v. AAR 379 ITR 256 (P&H) at p. 285. However, c/f Article 13(1) of Bangladesh-UK DTAA under which capital gains arising out of alienation of shares in a company that has immovable property will be taxed in the country in which such immorable property is situated 12 OECD (2015), Addressing the Tax Chullenges of the Digital Economy, Action 1 – 2015 Final Report, OECD/G20 Base Erosion and Profit Shifting Project, OECD Publishing, Paris, at p. 55, para. 117 ** Base Erosion and Profit Shifting Project of G 20 and OECD (the OECD BEPS Project)

Bangladesh has a source-based taxation system and it is anticipated that tax issues of e-commerce based transactions would largely involve determination of permanent establishment of digital or e-commerce enterprises. Business conducted through a software owned by an enterprise that is installed on a server, which is not owned by it would not constitute a permanent establishment in Bangladesh!33 But §18(2)(d) does not deal with source taxation based on permanent establishment. The concept of permanent establishment is separately dealt with in $18(2)(a) of the Ordinance. 134 It seems that §18(2)(d) has captured the concept of “significant economic presence” for the digital economy as encapsulated in the 2015 Final Report on Action 1 of the OECD BEPS Project. Under the concept of “significant economic presence” a taxable presence in a country will be determined when a non-resident enterprise has a significant economic presence in a country on the basis of factors that evidence a purposeful and sustained interaction with the economy of that country via technology and other automated tools.!

The “significant economic presence” could be identified by employing a range of factors, one of which is “digital factor”36 under which factors like use of a local domain name, use of local digital platform or use of local payment options by the non-resident enterprise could be used as part of a test to determine signifcant economic presence. The words “sale by any electronic means to purchasers in Bangladesh” in §18(2) (d) indicate identification of “digital factors” to determine significant economic presence for the purpose of taxation of non-resident digital or e-commerce entities.

Thus, for example, if a foreign digital company’s customers are located in Bangladesh, access the website in Dhaka, communicate their acceptance to the offer of merchandise advertised on the website, in Dhaka, and receive the merchandise in Dhaka, it could be argued that such transactions satisfy the words “sale by any electronic means to purchasers in Bangladesh” in §18(2) (d) and the “digital factors” indicated in the 2015 Final Report on Action 1 of the OECD BEPS Project137 could be used to identify the “significant economic presence” of that foreign digital company in Bangladesh even though the server for such foreign company’s website is not located in Bangladesh 138 It is interesting to note that the “digital factors” as described in the preceding example would also satisfy the requirement of the expression “carries on business” for the purpose of determining jurisdiction of the court under non-tax statutes like the Copyright Act 2000.139 Thus, if a foreign digital company uses a local domain name or a local digital platform to sell its goods or services to customers located in Bangladesh, then such transactions through the local website or “app” in Bangladesh could virtually be treated as the same thing as a seller having shops in Bangladesh,140 In other words, if a non-resident digital or e-commerce enterprise has “substantial virtual connections” to Bangladesh, it can be taxed for its income under $18(2)(d) of the Ordinance.141

Source of income-intangible property used in Bangladesh (518(2)(e)):

This sub-section creates a nexus between the use of the intangible property in Bangladesh and the resulting income from such use. Under §18(2)(e), physical presence of the non-resident enterprise or person is irrelevant and income will be deemed to accrue or arise in Bangladesh through or from the use of the intangible properties (for example, intellectual property rights) in Bangladesh because by or allowing such use of the intangible property in Bangladesh, the non-resident enterprise or person would be regarded as making “purposeful efforts to reap economic benefits” from Bangladesh.’42 Thus, a non-resident enterprise or person collecting income from a licensing agreement under which the intangible property will be used in Bangladesh would give rise to substantial nexus in Bangladesh despite the fact that the non-resident enterprise or person does not have any physical presence in Bangladesh.

Source of income-dividend paid outside Bangladesh by a Bangladeshi company (§18(3)): A Bangladeshi company must have its registered office in Bangladesh.’* Under the Companies Act 1994, the share register is kept at the registered office of the company!45 The situs of shares is the place where the share register is kept’46 or the place where the company is domiciled.’ Thus, dividend declared by a Bangladeshi company would be deemed to accrue in Bangladesh under 518(3)’48 or under $18(2)(b)49 for having the source of such dividend in Bangladesh and it is immaterial that such dividend is paid in respect of any credit facility which has not been utilised. It also includes interest on an unpaid purchase price payable under a letter of credit. 150

Source of income-fees for technical services (§18(5)):

The words “fees for technical services” (FTS) are defined in S2(31) of the Ordinance. The definition of “fees for technical services” is only for the purpose of this sub-section and $33 of the Ordinance and cannot apply to a Double Taxation Avoidance Agreement (DTAA) made under $144 of the Ordinance unless expressly so provided, Isl Due to the non-obstante clause of $144 of the Ordinance, FTS will not be charged to tax under $18(5) if the relevant DTAA stipulates non-chargeability. Under §18(5)(a) and (b), the expression “fees are payable in respect of services utilised” in Bangladesh means that if fees are paid for services utilised by the Bangladeshi company in its business carried on by it in Bangladesh, such fees will be deemed to accrue or arise in Bangladesh regardless of the place where the services are “rendered”

Thus, if services are utilised in Bangladesh for which fees are incurred abroad, such payment would be regarded as FTS because the services are utilised in a business carried on in Bangladesh. 153 Similarly, if any analysis report (prepared in a foreign country) is utilised in Bangladesh in connection with a business in Bangladesh and if the analysis of sample is undertaken in another country and payment is also made from abroad, then the payment for such analysis would be income accruing or arising in Bangladesh and withholding tax would need to be paid for such payment.154 But if any service is utilised for a business carried on by a resident person outside Bangladesh, then Services that are FTS: FTS includes payment for services provided by an assessee through its employees 56, success fee based on total debt financing raised by the financial advisor!s, fees for mud- testing15, fees for legal advice, tax advice, information technology advice!°, and fees for feasibility study.!60

Services that are not FTS: Fees for promotion of goods outside Bangladesh’®, commission for taking orders from overseas buyers’62, payment made to foreign employees as salaries for their services provided in Bangladesh’, fees for availing market development support service, fees for handling paperwork’6, and payment for purchase of bandwidth. 166

Source of income-royalty (§18(6)):

The word “royalty” is defined in $2(56) of the Ordinance. A payment that is chargeable as capital gains is excluded from the meaning of the term “royalty”. If the use of any patent, design, trademark, know-how or knowledge is incidental, the payment cannot be regarded as royalty!6 To categorise a payment under royalty, it is important to see the dominant or primary intention under the contract. If the payment is made to acquire the things listed in $2(56) of the Ordinance (rights in patent, information, etc.) for the purpose stipulated therein (use or working of patent, acquisition of technical skills, etc.), then such payment will be royalty. Thus, where the payment is for purchase of hardware and not the software per se, as the software is embedded in the hardware, such payment will not be royalty!68 Payment made for purchase of a software which is to be resold in the Bangladesh market is not royalty!69 Subscription fees paid to access a database does not amount to “use of” or “right to use of (for example, a licence)” copyright of a literary or scientific work’70 and it also does not amount to “information concerning technical, industrial, commercial, or scientific knowledge”7 because the information in the database are generally available in the public domain and are sold after being collected and compiled. However, if the data is customised for the client’s needs and business, then the subscription fee will be regarded as royalty.

What is royalty:

Payments received for supply of drawings and designs for building a bridge, or for sharing of specialist knowledge of a particular commodity!, or for supplying know-how necessary for setting up a plant!, or for use of patents'”, or for right to use intellectual property and know-how 78 are royalty. Under Explanation 1 to $2(56) of the Ordinance, clarity is brought to the words

“ownership”, “control” and “use” in the context of any right, property or information.

royalty in respect of any right, property or information, it is not necessary that (a) the payer of the royalty possesses or controls such right, property or information; (b) the payer directly uses such right, property or information; or (c) such right, property or information is in Bangladesh. In other words, if a third party uses, controls or possesses any right, property or information for which payment is made by the Bangladeshi company and if such right, property or information is not situated in Bangladesh, even then such payment would be regarded as royalty! Under Explanation 2 to 52(56) of the Ordinance, it is clarified that payment made to acquire bandwidth is regarded as royalty!80 Also, as per Explanation 2 to $2(56), the element of “secrecy” in the “process” under S2(56)(c) of the Ordinance is not required in case of payment for transmission by satellite (including up-linking, amplification, conversion for down-linking of any signal), cable, optical fibre or by any other similar technology.