How to approach ARBITRATION IN CHINA for Bangladeshi companies

In an increasingly interconnected global economy, Bangladeshi companies are expanding their horizons, engaging in international trade, and forming partnerships with entities from around the world. While these opportunities offer immense growth potential, they also bring about the possibility of disputes and disagreements. To address these challenges, Bangladeshi companies are turning to international arbitration, and one notable institution is gaining prominence – the China International Economic and Trade Arbitration Commission (CEITAC).

The Chinese legal framework has historically distinguished between local and international arbitration. However, the roles of domestic arbitration institutions in foreign-related disputes and foreign-related arbitration institutions in domestic conflicts have lately expanded.

Legal foundation

The People’s Republic of China (PRC) 1 Arbitration Law was issued on August 31, 1994, by the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress of the PRC, and entered into force on September 1, 1995 (1994 PRC Arbitration Law). It was updated on September 1, 2017, and the new version went into effect on January 1, 2018 (PRC Arbitration Law).

In the People’s Republic of China, civil legal problems that are not resolved by pre-action consultations between the parties can be handled through litigation or arbitration. If the parties do not otherwise agree, the PRC People’s Courts will have jurisdiction over civil cases, according to article 6 of the PRC Civil Procedure Law of 1 July 2017 (PRC Civil Procedure Law).

For foreign parties and foreign-invested businesses (FIE) 2 in the PRC, arbitration is the preferred method of dispute settlement for the following reasons:

Proceedings in ordinary PRC People’s Courts can be dangerous, especially for foreign parties and FIEs. Judges may be inclined to follow the orders of PRC administrative organizations, which may or may not safeguard the interests of the local party;

While it is theoretically possible under PRC law to agree to submit a dispute to the jurisdiction of a foreign court, judgments from the PRC’s major western trading partner countries are still not recognised and not enforceable in the PRC due to a lack of reciprocity between the PRC and these countries;

The major arbitration institutions in the PRC provide online arbitration, which allows the parties to conduct their arbitrations online (the parties must expressly agree to use online arbitration procedures).

Unlike most PRC People’s Court processes, 4 arbitration is usually held in private unless the parties agree otherwise; and

Arbitration also provides parties with greater flexibility in terms of procedures and formalities, such as the adoption of proceedings in a foreign language, 5, whereas litigation in the PRC must be performed in Chinese.

Distinctions between domestic, foreign-related, foreign arbitration, and arbitration administered by foreign arbitration institutions based in the People’s Republic of China

There are important distinctions to be made between domestic arbitration, foreign-related arbitration, foreign arbitration, and arbitration administered by foreign arbitration institutions headquartered in the PRC. These notions evolved independently throughout time, and the PRC Arbitration Law, as mentioned in paragraph 3.1.1 below, maintains a distinction between how domestic arbitration and foreign-related arbitration are treated under PRC law.

Domestic conciliation

Domestic arbitration rules apply in all cases when there are no foreign interests 6 engaged in the dispute.

Arbitration involving foreign parties

Foreign-related arbitration rules apply in cases where there is a “foreign interest” in the dispute.

Although there is no definition of “foreign-related arbitration” in the PRC Arbitration legislation, the word “foreign interest” can be found in other sources of PRC legislation.

According to article 522 of the Supreme People’s Court (SPC) Interpretation on the Application of the Civil Procedure Law in effect since 4 February 2015 (CPL Interpretation) and article 1 of the Interpretation of the Supreme People’s Court on Several Issues Concerning the Application of the People’s Republic of China Law on Foreign-Related Civil Relations:

(I) SPC Interpretation (ii) in effect since 7 January 2013, a dispute involving a “foreign interest” with Foreigners, foreign entities, or foreign organisations make up one or both of the parties.iii) One or both parties have their normal abode outside of the PRC’s borders;iv) The legal conditions surrounding the establishment, modification, or termination of a contractual connection occurred in a foreign country;v) the dispute’s subject matter is located in another country; orvi) Other situations may lead to a case being classified as a foreign-related dispute.

FIEs are firms that are incorporated under PRC regulations and are completely or partially funded by foreign investors, including wholly foreign-owned enterprises (WFOEs) and Sino-foreign joint venture enterprises (JVs) that are PRC domestic entities. 8 Unless any of the circumstances listed in paragraph 1.2.4 apply, any arbitration between a FIE and a PRC company or two FIEs is considered domestic and governed by the provisions of the PRC Arbitration Law that apply to domestic arbitration rather than foreign-related arbitration. The fact that a FIE is backed by a foreign investor does not automatically turn the issue into one involving “foreign interest.

Foreign Arbitration in China

Foreign arbitration rules apply where there is a dispute with a foreign interest that is administered by a foreign arbitration organization 9 or when an ad hoc arbitration takes place outside of the PRC.

According to Article 271 of the PRC Civil Procedure Law, foreign-related issues may be referred to a foreign arbitration organization for resolution. Arbitration clauses without a foreign interest in which a foreign arbitration was agreed by the parties have nearly always been treated as illegal by the court, including conflicts between a FIE and a domestic party, or between two FIEs, according to judicial experience. Traditionally, the fact that a FIE is sponsored by a foreign investor was insufficient to change the issue into one involving “foreign interest.

The case Siemens International Trading (Shanghai) Co. v Shanghai Golden Landmark Co., Ltd, (2013) Hu Yi Zhong Min Ren (Wai Zhong) Zi No.2 established the first exception to this doctrine. In this instance, the parties, two WFOEs registered in the PRC, submitted their contractual disputes for arbitration to the Singapore International Arbitration Centre (SIAC), and the arbitral ruling was rendered in Singapore.

However, the contract’s delivery location and subject matter were both in the PRC. The contract lacked any of the openly specified foreign interests mentioned in paragraph 1.2.4.

Nonetheless, the foreign arbitral award was recognized and enforced by Shanghai Municipality’s No. 1 Intermediate People’s Court. The court stated that there was a “foreign interest” involved because both parties were WFOEs incorporated in a Shanghai free trade zone (FTZ). The court went on to say that because the FTZ’s goal was to facilitate foreign investment, this should be taken into account when determining whether a “foreign interest” existed.

With effect on December 30, 2016, the Supreme People’s Court’s Opinions on Providing Judicial Safeguard to the Construction of FTZs (SPC FTZ Opinions) confirmed the special handling of WFOEs in FTZs.

According to article 9 of the SPC FTZ Opinions, if WFOEs registered in the FTZs agree to refer commercial disputes between them to a foreign arbitration institution for arbitration, the arbitration clause will not be deemed invalid if the sole reason asserted is that the dispute does not involve a foreign interest. This means that as long as the dispute is between WFOEs located in one or more FTZs, it can be referred to international arbitration without requiring any extra foreign interest.

This principle, however, does not apply to JVs registered in FTZs, nor to WFOEs or JVs registered outside of FTZs.

Article 9 of the SPC FTZ Opinions further states that where one or both parties are FIEs (including WFOEs and JVs) registered in the FTZs and agree to submit commercial disputes to a foreign arbitration institution for arbitration, the arbitration clause shall not be invalidated and enforcement of the arbitral award shall not be denied after the relevant foreign arbitral award is made.

Alternatively, if the other party did not object to the validity of the arbitration clause during the arbitration proceedings, it is not permissible to claim that the arbitration clause is invalid after the relevant foreign arbitral award is made on the grounds that the dispute does not involve a foreign interest. It is important to note, however, that the arbitration clause can be disputed during the arbitration proceeding, i.e. before the foreign arbitral judgement is issued.

Arbitration administered by international arbitral institutes with a presence in the PRC

As mentioned in a paragraph above, foreign arbitration refers to arbitration conducted outside of the PRC by foreign arbitration institutions or ad hoc arbitration. Recently, there has been a tendency toward allowing foreign arbitration institutes to handle disputes on PRC territory.

Previously, an arbitration clause providing for foreign arbitration before a foreign arbitration institution to be held in the PRC was unlikely to be considered valid under PRC law. Recent case law, on the other hand, suggests that the PRC courts may be pro-arbitration.

Longlide Packaging Co. is an example of this. In Longlide Ltd v BP Agnati SRL SPC 2013 Min Ta Zi No.13 (Longlide Case), a dispute arose over the validity of an arbitration clause that provided for any contractual dispute to be arbitrated before the International Chamber of Commerce (ICC), with the seat of arbitration in Shanghai, PRC.

The validity of the arbitration clause was challenged on the grounds that the ICC was a foreign arbitration institution that was not recognized as an arbitration commission The SPC, on the other hand, ruled that the arbitration clause was lawful since all of the requirements of Article 16 of the PRC Arbitration Law were met. This approach was replicated in the case of BNB v BNA (2020) Shanghai 01 Civil Special 83 (BNB Case), in which the arbitration provision required any contractual disagreement to be brought to the SIAC for arbitration in Shanghai.

The arbitration clause’s legitimacy was contested on the basis that PRC legislation precluded a foreign arbitration institution from administering a PRC-seated arbitration. However, the No. 1 Intermediate People’s Court of Shanghai Municipality upheld the arbitration clause since there was no specific PRC statute prohibiting international arbitration organizations from running PRC-seated arbitrations. 15

ARBITRATION INSTITUTIONS’ ROLE

Ad hoc arbitration inside the People’s Republic of China:

Article 16 of the PRC Arbitration Law requires an arbitration agreement to include a designated arbitration institution that will administer the arbitration in order for it to be legitimate and enforceable. In any case, this obligation applies to PRC domestic arbitration.

This condition also applies to foreign-related PRC arbitration unless the arbitration clause is effectively governed by a foreign law. According to article 16 of the Supreme People’s Court Interpretation on Certain Issues Concerning the Applicability of the People’s Republic of China Arbitration Law of 23 August 2006, effective as of 8 September 2006 (Interpretation), which was revised on 16 December 2008 and took effect on the same day, the laws agreed upon by the parties shall apply to a court’s examination of the validity of an arbitration agreement involving a foreign interest.

As a result, for foreign-related arbitration in which the parties have either chosen PRC law as the governing law of the arbitration agreement or are silent on the governing law of the arbitration clause, the PRC Arbitration Law applies, including article 16 which bars ad hoc arbitration.

Article 16 of the PRC Arbitration Law applies only if the parties chose PRC law as the governing law for the arbitration clause in foreign arbitration, including ad hoc foreign arbitration performed outside of the PRC.

For arbitration administered by foreign arbitration institutions seated in the PRC, if the parties chose PRC law as the governing law for the arbitration clause or are silent on the governing law for the arbitration clause, 17 article 16 of the PRC Arbitration Law also applies, according to recent relevant case precedents. 18

In general, an arbitration agreement providing for ad hoc arbitration within the PRC will be considered invalid (for failing to meet the requirements of PRC Arbitration Law article 16) but will not prevent a PRC People’s Court from accepting jurisdiction to hear a dispute between the parties to it. As a result, ad hoc arbitration in the PRC is uncommon.

For firms incorporated in FTZs, the limitation on ad hoc arbitration within the PRC was lifted some years ago. According to Article 9 of the SPC FTZ Opinions, if enterprises in the FTZs agree to settle their disputes at a specified location within the PRC, according to certain arbitration rules, and by specified arbitrators (as is typical of ad hoc arbitration), the arbitration agreement can only be ruled invalid with the SPC’s approval.

Domestic arbitral tribunals (arbitration commissions)

It is widely accepted that the term “arbitration commission” in the PRC Arbitration Law refers to the more regularly used term “arbitration institution.” Commentators have concluded that the reference to a “arbitration commission” in article 10 of the PRC arbitral Law refers to an arbitration institution formed in the PRC.

Prior to the implementation of the PRC Arbitration Law in 1994, domestic arbitration organizations were not independent of government authorities.

The PRC Arbitration Law of 1994 sought to reform arbitration in the PRC, transforming it into a more commercial form of conflict settlement free of judicial and administrative intervention. As a result, the structure of domestic arbitration institutions was changed, and any domestic arbitration institutions that did not comply with the stipulations of the PRC Arbitration Law of 1994 were closed down.

Under the PRC Arbitration Law, domestic arbitration institutions may be established directly under the provincial governments of provinces and autonomous regions 20 and are organized at the provincial level by the local Chamber of Commerce. They may be developed in other municipalities with districts as well. 22 However, in contrast to prior laws that governed the construction of arbitration institutions, the PRC Arbitration Law clearly states that domestic arbitral institutions must be autonomous of administrative agencies. Domestic arbitral institutions and administrative authorities shall not have submissive relationships. 23

Since the 1994 PRC Arbitration Law went into effect, the PRC has established over 200 domestic arbitration institutions, including the Beijing Arbitration Commission, Shanghai Arbitration Commission, Guangzhou Arbitration Commission, Shenzhen Arbitration Commission, and Wuhan Arbitration Commission.

According to article 3 of the Notice of the General Office of the State Council on Several Issues That Need to Be Clarified in Order to Implement the People’s Republic of China Arbitration Law (issued in 1996), domestic arbitration institutions may also administer foreign-related disputes if the parties agree.

While the statute demands a rigorous legal separation between administrative authorities and domestic arbitration institutions, it should be highlighted that these legal safeguards are not always successful in practice. Domestic arbitration organizations are not all immune from court and administrative intervention. Local protectionism and political clout are typical issues. Parties that are concerned about these issues frequently choose to use a foreign arbitration institution (if available) or a respectable, foreign-related arbitration commission (such as CIETAC, which is mentioned more below at paragraph 2.3.4).

Foreign-affiliated arbitral institutions

Foreign-related arbitration organizations were established in the PRC to handle foreign-related disputes.

In contrast to the organizational structure of domestic arbitration institutions, the China International Chamber of Commerce is required under the PRC Arbitration Law to organize and develop foreign-related arbitration institutions.

There is a distinction between the ways in which domestic and foreign-related arbitration organizations run arbitral procedures in terms of who can be appointed as arbitrator by such institutions. Arbitrators may be appointed by foreign-related arbitration institutions from “among foreigners with special knowledge in the fields of law, economy and trade, science and technology, and so on.” Domestic arbitration institutions, on the other hand, must designate arbitrators who are “fair and honest” and meet at least one of the qualifications mentioned in article 13 of the PRC Arbitration Law. This indicates how a domestic arbitration organization has less flexibility and autonomy in some circumstances than a foreign-related arbitration institution.

The China International Economic and Trade Arbitration Commission (CIETAC), created in 1956 to resolve economic and trade disputes between a foreign entity and a PRC firm, is the most well-known foreign-related arbitration institution. CIETAC is also one of the world’s largest arbitration centers.

It is headquartered in Beijing, with Sub-Commissions in Shenzhen (also known as the South China Sub-Commission and founded in 1989), Shanghai (founded in 1990), Tianjin (founded in 2008), Chongqing (founded in 2008), Zhejiang (founded in 2015), Hubei (founded in 2015), Fujian (founded in 2017), Sichuan (founded in 2018), and Shandong (founded in 2018). CIETAC has founded the Hong Kong Arbitration Centre (in 2012), the Jiangsu Arbitration Centre in Nanjing (in 2017), the Silk Road Arbitration Centre in Xi’an (in 2018), and the Hainan Arbitration Centre (in 2020).

2.3.5 On August 4, 2012, the CIETAC Shanghai Sub-Commission and the CIETAC South China Sub-Commission announced their intention to become autonomous arbitration organizations.

On 22 October 2012, the CIETAC South China Sub-Commission was renamed the South China International Economic and Trade Arbitration Commission (SCIETAC) or the Shenzhen Court of International Arbitration (SCIA), which then merged with the Shenzhen Arbitration Commission (SAC) on 25 December 2017 to form the Shenzhen Court of International Arbitration (Shenzhen Arbitration Commission) (SCIA-SAC).

The Shanghai International Economic and Trade Arbitration Commission (SIETAC), formerly known as the Shanghai International Arbitration Centre (SHIAC), was renamed the Shanghai International Economic and Trade Arbitration Commission (SIETAC) on April 11, 2013. The withdrawal from CIETAC and name change by both sub-commissions, known as the “CIETAC Split,” generated uncertainty in arbitration agreements that referred to both sub-commissions as the administering institutions.

To address this, on 15 July 2015, the Supreme People’s Court issued the Official Reply of the Supreme People’s Court on the Request of the Shanghai High People’s Court and Others for Instructions on Cases Involving the Judicial Review of Arbitral Awards Made by China International Economic and Trade Arbitration Commission, Its Former Sub-Commissions, and Other Arbitration Institutions, a binding judicial interpretation that took effect on 17 July 2015 (SPC Reply).

The SPC Reply clarified that if the arbitration agreement naming CIETAC Shanghai Sub-Commission or CIETAC South China Sub-Commission as the arbitration institution was signed before the former CIETAC Shanghai Sub-Commission was renamed SHIAC, i.e. 11 April 2013, or before the former CIETAC South China Sub-Commission was renamed SCIA, i.e. 22 October 2012, SHIAC or SCIA should have jurisdiction.

If an arbitration agreement naming CIETAC Shanghai Sub-Commission or CIETAC South China Sub-Commission as the arbitral institution was signed after the former CIETAC Shanghai Sub-Commission was renamed SHIAC or the former CIETAC South China Sub-Commission was renamed SCIA, CIETAC should have jurisdiction.

Prior to the introduction of the PRC Arbitration Law in 1994, the only arbitration institutions in the PRC eligible to conduct foreign-related arbitration procedures were CIETAC and the China Maritime Arbitration Commission (CMAC). 28 These two arbitration organizations survived the modifications enacted by the PRC Arbitration Law in 1994 and continue to exist apart from domestic arbitration institutions.

Despite the fact that local arbitration institutions can now hear international cases, CIETAC maintains its leadership position in international arbitration by hearing a large number of cases. Furthermore, CIETAC and CMAC have expanded its range of competence to include both internal and international issues, if the parties so agree. 29 CIETAC arbitration is governed by the CIETAC Arbitration Rules. These guidelines have been changed multiple times over the years.

The most recent modification, which took effect on January 1, 2015, included additional amendments to modernize the CIETAC Arbitration Rules. The new guidelines apply to CIETAC Beijing arbitrations as well as those overseen by its various sub-commissions. The revised regulations also include unique provisions for CIETAC Hong Kong Arbitration Centre-administered arbitration hearings.

On September 19, 2017, CIETAC issued the China International Economic and Trade Arbitration Commission’s Arbitration Rules for International Investment Disputes (for Trial Implementation), which went into effect on October 1, 2017. This is the first set of arbitration rules developed by CIETAC for international investor-state investment disputes.

Due to the recent expansion of the roles of both domestic arbitration institutions (into foreign-related disputes) and foreign-related arbitration institutions (into domestic disputes), the traditional distinction between these two types of arbitration institutions has become significantly blurred. The increased competition between foreign-related and certain domestic arbitration institutions, which can be expected to result in an improvement in the quality of arbitration in the PRC, is a positive feature of this trend.

As a result of this development, the primary distinction between domestic and foreign-related arbitrations under the PRC Arbitration Law is now the nature of the underlying dispute, rather than the arbitration institution that is managing the arbitral procedures. This disparity is especially noticeable in the enforcement of awards.

Foreign arbitral tribunals

There is no legislative definition of “foreign arbitration institutions” in the People’s Republic of China. The term “foreign arbitration institution” is thus understood to refer to arbitration institutions based outside of the PRC, such as the ICC, Hong Kong International Arbitration Centre (HKIAC), SIAC, Stockholm Chamber of Commerce (SCC), Zurich Chamber of Commerce (ZHK), German Institution of Arbitration (DIS), London Court of International Arbitration (LCIA), and World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) Arbitration and Mediation Centre, among others.

Foreign arbitration organizations based in the PRC

Foreign arbitration institutions have traditionally been prohibited from operating in the PRC because article 10 of the PRC Arbitration Law requires the prior approval of the administrative department of justice of the relevant province, autonomous region, or municipality directly under the central government.

However, things have just begun to alter. The State Council of the People’s Republic of China issued the Framework Plan for the New Lingang Area of China (Shanghai) Pilot FTZ on July 27, 2019, allowing well-known overseas arbitration and dispute resolution institutions to establish business divisions in the Lingang FTZ in Shanghai to conduct arbitration in civil and commercial disputes arising in international commerce, maritime, investment, and other fields. The Measures for the Administration of the Establishment of Business Offices by Overseas Arbitration Institutions in Lingang New Area of China (Shanghai) Pilot FTZ, which went into effect on 1 January 2020, were announced on 19 October 2019.

They govern the establishment of overseas arbitration institutions in the Lingang New Area of China (Shanghai) Pilot FTZ, which refers to non-profit arbitration institutions legally established in foreign countries, the Hong Kong and Macao Special Administrative Regions, and the Taiwan Region of China, as well as arbitration institutions established by international organizations that the PRC has authorized to conduct arbitration business.

The Supreme People’s Court Opinions on Providing Judicial Services and Safeguards for the Construction of the Lingang Special Area of the China (Shanghai) Pilot FTZ by People’s Courts were published and became effective on December 13, 2019. They assist registered overseas arbitration organizations in handling civil and commercial disputes in international commercial, maritime, investment, and other domains in the Lingang Special Area. 33 Regulations on the Shanghai Court Services to Ensure the Implementation of the Lingang Special Area of China (Shanghai) Pilot FTZ were issued on December 30, 2019, and went into effect on the same day.

They provide assistance to international arbitration and conflict resolution institutes that have been legally registered and filed for business. 34 Several Policies for the Promotion and Development of the Legal Services Industry in the Lingang New Area of China (Shanghai) FTZ were published on May 19, 2020. They were amended on September 29, 2020, and became effective on October 1, 2020, valid through December 31, 2022. These policies apply to domestic or international legal service institutions with their registered office, actual place of business, and fiscal and tax account administration in Lingang New Area.

Aside from Shanghai, Beijing is also welcoming foreign arbitration institutes. The Work Plan for A Deepening Comprehensive Pilot and New Round of Opening-Up of Services Sectors in Beijing and Building a Comprehensive Demonstrative Area of Opening-Up of State Services Sectors was published by the State Council of China on September 7, 2020. According to this policy paper, foreign arbitration institutions will be permitted to establish business organizations in specific districts of Beijing to provide arbitration services in civil and commercial disputes originating in international commerce and investment.

On 20 October 2019, the Ministry of Justice formally approved WIPO’s Shanghai Centre for Arbitration and Mediation, which will be established and operational on 20 October 2020. This is China’s first overseas arbitration organization, and it will hear its first foreign-related intellectual property dispute in July 2020.

THE PRC ARBITRATION LAW’S SCOPE OF APPLICATION AND GENERAL PROVISIONS

Application Scope

3.1.1 The PRC Arbitration Law retains a “dual track system,” 37 which distinguishes between domestic and foreign-related arbitration, while in practice the distinction is blurring. 38 Special provisions for foreign-related arbitration are found in Chapter VII of the PRC Arbitration Law. Where topics arising from an arbitration are not expressly covered by Chapter VII, the remaining provisions of the PRC Arbitration Law apply to all arbitral procedures held in the PRC. 39 In practice, the arbitration rules of the relevant arbitration institution are more detailed and supplement the provisions on the arbitration procedure described in the PRC Arbitration Law (for example, the CIETAC Arbitration Rules, which are the most commonly used institutional arbitration rules for foreign-related disputes).

3.1.2 Foreign arbitrations and arbitrations administered within the PRC by foreign arbitration institutions are rule-based, with the controlling law chosen or the laws applicable at the seat of the arbitration and the arbitration institution’s rules as the foundation. 40

3.2 Overarching Principles

3.2.1 Although several sections reflect key concepts of modern international arbitration, such as procedural fairness and arbitrator independence, the PRC Arbitration Law is not based on the UNCITRAL Model Law (1985). 41 In contrast to the UNCITRAL Model Law (1985), the PRC Arbitration Law seeks to protect the “legitimate rights and interests of the parties and to ensure the healthy development of the socialist market economy.”

THE ARBITRATION CONTRACT

Formal prerequisites

Only if the parties to the dispute have agreed into a binding agreement to submit their dispute to arbitration can FIEs or domestic PRC parties avoid litigation before a PRC People’s Court. A legitimate arbitration clause in a contract or a separate, stand-alone arbitration agreement can be entered into before or after the dispute has arisen. If the parties have concluded a legitimate arbitration agreement in relation to the case in question, a PRC People’s Court must deny jurisdiction.

An arbitration clause in a contract, or a stand-alone arbitration agreement, must be in writing. 44 According to PRC legislation, “in writing” encompasses communication via letter, telegram, telex, fax, electronic data interchange, and email. 45 A reference to an arbitration clause in standard terms and conditions is adequate if the general terms and conditions have been properly incorporated into the contract.

When an arbitration clause in a contract differs from a supplemental agreement, the question of which clause will take precedence is determined by the facts of the case. The SPC held in the case of Hunan Huaxia Construction Co., Ltd. v. Changde School of Arts and Crafts [2015] Zhi Shen Zi No.33 that where a supplemental agreement is inseparable from the original agreement and lacks an arbitration clause or contains an arbitration clause that differs from that in the original agreement, the arbitration clause in the original agreement would prevail. However, if a supplemental agreement is independent of and distinct from the original agreement, even if it lacks an arbitration clause, the original agreement’s arbitration clause will not apply.

Article 16 of the PRC Arbitration Law Requirements

A valid arbitration agreement must include the following information:

- a declaration of desire to seek arbitration;

- the issues that have been assigned to arbitration; and

- an arbitral institution.

If the matters to be addressed in arbitration are not clearly stated in the arbitration agreement, and the parties do not clarify the position through a supplemental agreement, the arbitration agreement is deemed unlawful.

As stated in a paragraph above, ad hoc arbitrations are generally prohibited by the PRC Arbitration Law. In the PRC, there has long been debate about whether an arbitration agreement that only refers to the arbitration rules of a specific arbitration institution but does not expressly provide for administration by that institution constitutes a valid arbitration agreement.

The Interpretation provides guidance in situations where an arbitration agreement only contains arbitration rules without designating the administering arbitration institution, which could potentially invalidate the arbitration agreement under PRC Arbitration Law article 16

. The Interpretation specifically provides that where the name of an arbitration institution as stipulated in the arbitration agreement is not true but the specific arbitration institution can still be recognized, the arbitration institution is presumed to have been selected. 49 According to the Interpretation, an arbitration agreement is not void if the arbitral institution is explicitly identified by the arbitration rules contained in the arbitration agreement.

The Interpretation and its impact on possibly inadequate arbitration agreements suggest that the requirement that the parties specifically name an arbitration institution in their arbitration agreement may be relaxed under the PRC Arbitration Law. The Provisions of the Supreme People’s Court on Several Issues Concerning the Hearing of Cases Involving the Judicial Review of Arbitration of 26 December 2017, effective as of 1 January 2018 (SPC Provisions), also provide that where the arbitration institution or place of arbitration, though not explicitly specified in the arbitration agreement, could be determined under the applicable arbitration rules as specified in the arbitration agreement, the arbitration institution or place of arbitration shall be determined under the applicable arbitration rules as specified in the arbitration agreement. 51 Nonetheless, in order to establish the legitimacy of the arbitration agreement, parties should clearly select a competent arbitration institution to oversee the case in their arbitration agreement.

Despite the Interpretation, there is still a possibility that an arbitration clause that does not specifically name the arbitration institution may be invalidated in practice. The Shijiazhuang Intermediate People’s Court found the arbitration clause to be invalid in the case Automotive Gate FZCO v. Hebei Zhongxing Automobile Manufacturing Co., Ltd. (2011) Shi Min Li Cai Zi No. 00002 (FZCO Case) because the parties agreed in the arbitration agreement to apply the ICC arbitration rules and that the arbitration would be held in China, but did not agree on a specific arbitration institution, which did not satisfy the requirement.

Contractual Dispute Resolution

Contractual disputes and disagreements over property rights between citizens, legal persons, and other organizations are arbitrable under the PRC Arbitration Law. 52 FIEs can thus be parties to arbitral proceedings under the PRC Arbitration Law if they are lawfully incorporated as legal bodies. 53 In practice, most FIEs, such as Sino-foreign equity joint venture enterprises and WFOEs, are legally incorporated under PRC law.

According to the PRC Arbitration Law, the following conflicts are not arbitrable:

Disputes over marriage, adoption, guardianship, support, and succession; and

Administrative conflicts must be resolved by administrative organs under statutory laws. 54

Separation:

The validity of an arbitration clause contained in a contract is assessed separately from the validity of the contract itself. An arbitration agreement exists independently of the underlying contract and is unaffected by its change, revocation, termination, or invalidity.

In international arbitration practice, the arbitral tribunal normally determines the legitimacy of an arbitration agreement. However, the PRC Arbitration Law reserves this question for resolution by either the arbitration institution or the PRC People’s Court.

ARBITRAL TRIBUNAL COMPOSITION

Arbitral tribunal composition:

As agreed by the parties, an arbitral panel may consist of one or three arbitrators. 57 The PRC Arbitration Law makes no mention of what occurs if the parties cannot agree on the number of arbitrators. Depending on whether institutional arbitration rules apply, this question is treated differently.

If an arbitral tribunal consists of three arbitrators, both parties must choose one arbitrator or authorize the chair of the arbitration institution managing the arbitral proceedings to do so on their behalf. A third arbitrator will thereafter be chosen jointly by the parties or appointed by the chair of the arbitration institution in accordance with the parties’ joint mandate. The presiding arbitrator shall be the third arbitrator.

If the parties agree to a single arbitrator, that arbitrator shall be chosen jointly by the parties or nominated by the chair of the arbitration institution in line with the parties’ joint mandate. 59

If the parties are unable to reach an agreement on the method of formation of the arbitral tribunal or fail to select the arbitrators within the time limit specified in the applicable arbitration rules, the arbitrators will be appointed by the chair of the arbitration institution that is administering the arbitral proceedings. 60

Arbitral tribunal composition under the CIETAC Arbitration Rules

The arbitral panel shall be composed of one or three arbitrators under the CIETAC Arbitration Rules. Unless the parties agree otherwise, the arbitral tribunal will be composed of three arbitrators under the CIETAC Arbitration Rules.

The arbitral tribunal’s members are normally chosen by the parties from a panel of CIETAC arbitrators. As of 1 May 2017, the CIETAC panel of arbitrators included 1,449 arbitrators, including 434 non-PRC nationals from more than 40 countries. Non-PRC nationals can be appointed as arbitrators in foreign-related issues. 62 Parties may also appoint arbitrators who are not on CIETAC’s roster of arbitrators, but any such appointment must be confirmed by CIETAC’s chair.

In practice, the majority of arbitrators, including the arbitral tribunal’s chair, are normally PRC nationals. This is because CIETAC tends to designate PRC nationals as arbitrators when called upon to do so (for example, if CIETAC is serving as the appointing authority or if the parties cannot agree on an arbitrator).

Procedural Rules for Contesting and Replacing Arbitrators:

The parties may challenge an arbitrator in one of the following circumstances:

- The arbitrator is a party in the case, a close family of a party, or a representative of a party in the case;

- The arbitrator is involved in the case;

- The arbitrator has another contact with a party or a party’s agent in the case that may compromise the arbitrator’s impartiality; or

- The arbitrator has secretly met with a party or a representative of a party, or accepted an invitation to entertainment or a gift from a party or a representative of a party.

- A party shall submit its grounds for challenging the arbitration before the first hearing, or as soon as practicable if it becomes aware of a reason for challenging the arbitrator after the first hearing. If the reasons for the challenge became known after the start of the first hearing, an arbitrator’s challenge may be made before the conclusion of the arbitral tribunal’s final hearing.

- The chair of the arbitration institution will make the decision to remove an arbitrator, or if the head of the arbitration institution is also an arbitrator, the arbitration institution will make the decision jointly.

Following the removal of an arbitrator, a replacement arbitrator is appointed.

Following the appointment of a replacement arbitrator, a party may request that the arbitral tribunal hear the matter again. The arbitral panel will decide whether the arbitral proceedings should be continued or restarted. 68

Arbitration Request

Article 23 of the PRC Arbitration Law specifies the requirements for filing an arbitration request. The following information must be included in the arbitration request:

- the parties involved;

- the legal representatives of the parties;

- the registered addresses of the parties;

- the claimant’s arbitration claim, as well as the facts and reasoning supporting that claim; and

- Any evidence, the sources of evidence, and the names and addresses of any witnesses, if any.

The request for arbitration must include a copy of the arbitration agreement.

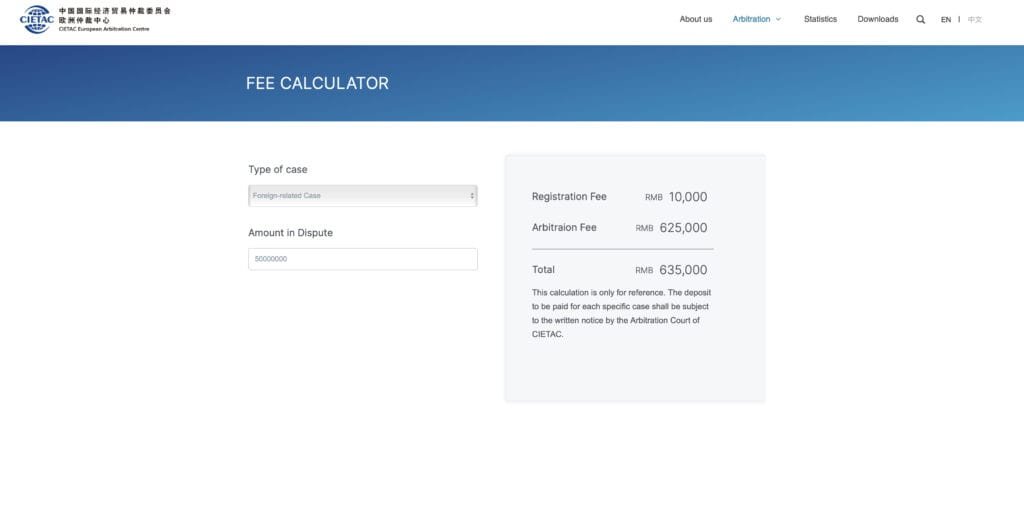

Fees for Arbitration

On July 28, 1995, the State Council promulgated the Arbitration Fee Collection Measures of the Arbitration Commission as part of the 1994 PRC Arbitration Law. As a general rule, the losing side must bear the arbitration fees under the Measures. 70 The arbitration expenses, according to the Measures, include case acceptance and case processing fees. The case management fees are used to cover the costs of paying the arbitrators’ fees and keeping the arbitration institution running.

The case handling fees include: (i) accommodation, transportation, and other reasonable expenses incurred by the arbitrators in handling the arbitration case due to business trips and hearing sessions; (ii) accommodation, transportation, and overtime subsidies for witnesses, expert witnesses, interpreters, and other personnel paid for appearing; (iii) expenses for consultation, appraisal, inspection, and translation; and (iv) expenses for consultation, appraisal, inspection, and translation. However, the arbitration rules of relevant foreign-related arbitration institutions have distinct fee schedules, which will apply if the parties choose such arbitration procedures. Section 8.4 discusses who is responsible for legal bills and other expenses.

ARBITRALTRIBUNAL JURISDICTION

6.1 Competence to make a decision on jurisdiction

6.1.1 The arbitration institution 71 is not the exclusive authority to determine the legitimacy of an arbitration agreement. 72 Either the arbitration institution or a PRC People’s Court can hear a request for a judgement on the legitimacy of an arbitration agreement. If one party requests a decision from the arbitration institution and the other party appeals to the PRC People’s Court for a judgement, the PRC People’s Court’s decision will take precedence. However, if a party fails to object to the validity of an arbitration agreement prior to the first oral hearing before the arbitral tribunal, or if an arbitration institution has made a decision on the validity of an arbitration agreement, the PRC People’s Court will not accept an application for a ruling on the same arbitration agreement’s validity. 73

The law that governs the arbitration agreement

6.2.1 The parties may pick the applicable legislation to the arbitration agreement and should do so explicitly, as this law may not be the same as that regulating the contract. According to the SPC Provisions, if the contract only specifies the law applicable to the contract and not the law applicable to determining the validity of a foreign-related arbitration agreement, the PRC People’s Court will not consider the law applicable to the contract when determining the validity of the arbitration provision. 74 In addition, the SPC Provisions take an arbitration-friendly approach: if the law of the place where the arbitration institution is located and the law of the place of arbitration have different laws and regulations on the validity of an arbitration agreement, the laws and regulations that find the arbitration agreement effective shall apply. 75

6.3 Authority to impose temporary measures

6.3.1 Either party may seek interim protective measures from a PRC arbitral tribunal. 76 However, neither the arbitral tribunal nor the arbitration institution in charge of the proceedings has the authority to mandate interim measures. Instead, it will refer the case to the PRC People’s Court, which has only competence to provide interim measures. Orders safeguarding property and evidence are among the interim protective measures available. 78 Since January 1, 2013, parties in civil litigation have been authorized to seek prohibitory and mandatory injunctions.

However, the PRC Arbitration Law is mute on the subject. As a result, it is unclear whether parties may seek an injunction in an arbitration proceeding. Since January 1, 2013, parties in civil litigation have been authorized to seek prohibitory and mandatory injunctions. The PRC Arbitration Law, on the other hand, is quiet on the subject. As a result, it is unclear whether parties may seek an injunction in an arbitral proceeding. 80

PROCEDURES CONDUCT

Arbitration commencement

Articles 24 and 25 of the PRC Arbitration Law contain certain procedural provisions on the initiation of arbitral proceedings, notably those requirements relating to the arbitration institution’s acceptance or refusal of the application for arbitration. After accepting an application for arbitration, an arbitration institution must notify the claimant within five days.

The arbitration institution must provide the claimant with a copy of the arbitration rules and the panel of arbitrators registered with the institution. It must also provide the respondent with a copy of the request for arbitration as well as information on the arbitration rules and the panel of arbitrators registered with the institution.

The respondent must submit a statement of defence and/or a counterclaim to the arbitration institution after receiving a copy of the application for arbitration. The claimant will then be served with a copy of the statement of defence and/or a counterclaim by the arbitration institution. The respondent’s failure to file a defense will have no effect on the progress of the arbitral proceedings.

A party may appoint either a PRC or a non-PRC national to act as its representative in the arbitral proceedings under the CIETAC Arbitration Rules. 84

Arbitration Language

The arbitral procedures shall be conducted in Chinese as a matter of principle under the CIETAC Arbitration Rules. The parties can, however, agree to have the arbitration proceedings in a foreign language. 85

Issues involving multiple parties

Under PRC law, for an arbitration agreement or arbitration clause to be effective, the parties must agree to it, and so only those parties who have expressly consented to send their dispute to arbitration will be bound by it. There are a few exceptions to this, which are detailed in the Interpretation, and they are as follows:

- In the event that two or more legal entities merge, the merged entity is bound by the arbitration agreements agreed into by its predecessor(s);

- If claims or obligations are transferred or assigned in whole or in part, the corresponding arbitration agreement will be binding on the transferee or assignee, unless the parties agree otherwise or the party is uninformed of the existence of a separate arbitration agreement; and

- If a party to an arbitration agreement dies, the arbitration agreement binds the beneficiary who succeeds to the deceased’s rights and obligations in arbitral cases.

Because there are no particular requirements in PRC law for a valid multi-party arbitration agreement, parties should adhere to the norms of the applicable arbitration institution selected to oversee their arbitral proceedings. To deal with many parties or contracts, article 19 of the most recent CIETAC Arbitration Rules, which became effective on January 1, 2015, gives CIETAC the authority to combine two or more arbitrations into a single arbitration if:

The arbitration claims are all made under the same arbitration agreement.

The claims in the arbitrations are brought under several identical or compatible arbitration agreements, and the arbitrations involve the same parties as well as legal relationships of the same type.

The claims in the arbitrations are brought under several similar or compatible arbitration agreements, and the multiple contracts involved include a principal contract and its ancillary contracts; or

All of the parties to the arbitrations have agreed to merge their proceedings. Furthermore, article 29 of the CIETAC Arbitration Rules includes a clause on multi-party tribunals, which states that when there are two or more claimants and/or respondents in an arbitration case, the claimant and/or respondent sides shall each jointly nominate or jointly entrust the chair of CIETAC to appoint one arbitrator following discussion.

Oral and written hearings and procedures

The PRC Arbitration Law also includes various procedural regulations pertaining to oral hearings and the awarding process. 89 In most cases, the arbitral tribunal will have an oral hearing to hear the arbitration; however, if the parties agree, the arbitral tribunal may conduct the arbitration solely on the basis of written submissions.

The arbitral panel conducts the oral proceedings, which are governed by the arbitration rules of the appointed arbitration institution. There is no guidance on whether the procedures should be conducted in a civil or common law format. Either is feasible, including the arbitration tribunal requesting evidence from both parties or gathering evidence itself. Expert witnesses may be requested by the arbitral tribunal or requested by the parties.

There will almost always be no common law discovery process. Both parties’ representatives may be permitted to make arguments and cross-examine the other party’s witnesses and experts. In the absence of an oral hearing, the arbitral ruling is based on the written submission, which includes the arbitration application, the defense statement, and other documents.

One of the parties defaults

If a claimant fails to appear before the arbitral tribunal for any reason, the arbitral tribunal may rule that the claimant has withdrawn the arbitration application. If a respondent fails to appear without reasonable cause, the tribunal may make a default award. If any party exits a hearing before it concludes, the same powers apply. 91

Maintaining Confidentiality

The arbitral tribunal shall not hold any public oral hearings. Except in cases involving state secrets, the arbitration may take place in public if the parties agree to it.

THE AWARDING AND THE END OF THE PROCEEDINGS:

Legal System Selection

Because the PRC Arbitration legislation is only a procedural legislation, it does not specify which substantive law should be applied to the dispute. This question is governed by the substantive law’s applicable rules and regulations

Contractual disagreements

Contractual disputes are governed by the law chosen by the parties, unless such a decision is prohibited. If the contract involves a foreign interest, the parties are free to agree on the controlling law, unless mandatory PRC law applies, according to the Law of the People’s Republic of China on the Application of Law in Foreign-related Civil Relations (Application Law). 94 There is no definition of a contract involving foreign interest in the PRC Civil Code.

The notion of a “dispute involving foreign interests” in article 1 of SPC Interpretation (I) 95 is typically applied in this context. In practice, this means that in most circumstances, a foreigner or foreign business must be a party to the contract in order for a foreign law to be permitted as the controlling law. In this sense, FIEs are not considered foreign parties 96, which means that a contract between a FIE and a PRC domestic company, or a contract between two FIEs, is normally subject to PRC law.

Mandatory PRC law states that some contractual transactions (and any disputes arising from such transactions) must be governed by PRC law, even if the contract involves a foreign interest, such as a foreigner or foreign entity. Contracts of this type include:

- agreements for Sino-foreign equity joint ventures;

- contracts for Sino-foreign joint ventures; and

- Contracts for Sino-foreign cooperation exploration and development of natural resources to be carried out on PRC territory.

In the absence of an agreed choice of law, the arbitral tribunal will adopt PRC law’s conflict of laws principles. In the absence of an agreed-upon ruling law, the legislation most closely associated with the foreign-related civil relationship shall rule. According to Articles 2 and 41 of the Application Law, if the parties did not choose the applicable law, the law of the habitual residence of the party who had the obligations to perform the part of the contract that most closely reflects the characteristics of the contract, or another law most closely associated with the contract, shall apply.

Non-contractual disagreements

In addition to contractual conflicts, some non-contractual issues, such as intellectual property infringement claims, can be arbitrated if both parties enter into a valid stand-alone arbitration agreement after the disagreement has arisen. The Application legislation specifies the legislation that applies to non-contractual issues. In a foreign-related civil relationship, the Application Law also confirms the parties’ ability to pick the applicable law. 99 However, the Application Law contains provisions requiring the application of a specific law, such as in the case of real estate property rights, negotiable instruments, and pledges.

Award timing, form, substance, and notification:

An award must state:

- the claim for arbitration;

- the realities of the conflict;

- the decision’s justifications;

- the award’s outcomes;

- the distribution of arbitral fees; and

- The date of the award.

If the parties agree that the facts of the dispute and the grounds for the decision should not be included in the award, such elements may be excluded. 104

Instead of requiring a unanimous vote of the arbitral tribunal, awards are decided by majority judgment of the arbitral tribunal. Dissenting arbitrators are permissible, but they are not required to sign the award. 106

During the arbitration, arbitral tribunals may make interim awards based on specific facts of the dispute that have become obvious. 107

According to the CIETAC Arbitration Rules, in foreign-related disputes, the award must be issued within six months of the day the arbitral panel was formed. The President of the Arbitration Court may extend this time limit at the request of the arbitral panel if he or she believes it is truly required and the reasons for the extension are justified.

Agreement:

- The arbitral tribunal may recognize settlement agreements reached between the parties by issuing an award containing the parameters of the settlement or issuing a written conciliation statement. 109

- The authority to award interest and fees

- In arbitral procedures, the losing party is normally responsible for the winning party’s reasonable legal fees. This is in contrast to litigation in the PRC, where, with the exception of some conflicts affecting the protection of intellectual property rights, the winning party is normally responsible for its own legal bills. In extraordinary circumstances, the arbitral tribunal may award the winning party additional and other reasonable expenses.

There may be interest awarded. The interest rate will be determined by the applicable law to the case. The arbitral tribunal has the authority to grant or deny interest on claims awarded to the winning party.

Closure of the proceedings:

- Arbitral procedures can be terminated by default or settlement, in addition to a final award.

- The Award’s Impact

- The award takes effect and becomes legally binding on the day it is made. 111

- Correcting, clarifying, and issuing an additional award

- If the award contains typographical or mathematical mistakes, or omits certain elements to be decided by the arbitral tribunal, the parties may request a rectification within 30 days of receiving the award. 112 If the award omits whole claims, the parties may request a supplementary award.

THE COURTS’ ROLE

Court of Appeal Jurisdiction:

The PRC People’s Court’s role in arbitration is to challenge and enforce awards, as described in section 10 below, and to issue interim measures, as described in section 9.3 below.

Stay of procedures and jurisdictional rulings:

If a party files a case in the PRC People’s Court after concluding an arbitration agreement, the PRC People’s Court will not accept the case unless the arbitration agreement is invalid. 113 In the event of a dispute over the validity of an arbitration agreement, either the PRC People’s Court or the arbitration institution shall rule; if one party requests the PRC People’s Court to rule and the other the arbitration institution, the PRC People’s Court shall rule.

Protective measures in the interim:

If a party requests temporary property preservation measures in an arbitration, the relevant arbitration institution is required to submit the application to the competent People’s Court in the location of the property. If a party seeks temporary measures of evidence preservation in a domestic arbitration, the relevant arbitration institution shall submit the application to the competent Basic People’s Court in the location of the property. 116 If a party seeks temporary measures of evidence preservation in a foreign-related arbitration, the appropriate arbitration institution shall submit the application to the competent Intermediate People’s Court in the location of the property.

According to Article 77 of the CIETAC Arbitration Rules, an arbitral tribunal may order its own interim measures at the request of a party. The arbitral tribunal may additionally request that security be provided in connection with the temporary measure.

Although article 77 of the CIETAC Arbitration Rules appears to allow parties to seek interim relief outside the PRC courts, there is a problem with enforcement. Because there is no legislation providing the legal basis for PRC courts to enforce interim remedies ordered by a CIETAC arbitral panel, such interim measures have limited practical utility.

Article 77 of the CIETAC Arbitration Rules is expected to apply limited to matters administered in Hong Kong within Greater China (i.e. the PRC and the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region). Article 45 of the Hong Kong Arbitration Ordinance (which has been in effect since 1 June 2011) provides that Hong Kong courts have both legal competence and jurisdiction to award interim measures to aid the course of an arbitral procedure.

CHALLENGING AND APPEALING AN AWARD IN COURT

Representations

It is not possible to appeal an award before an arbitral tribunal or the People’s Court of the People’s Republic of China.

Requests to Reserve an Award:

Domestic arbitration award.

While there is no right of appeal, awards given by an arbitral tribunal in the PRC relating to domestic disputes can be set aside by a competent Intermediate People’s Court under certain situations.

The appropriate Intermediate People’s Court will be the court in the location of the arbitration institution that oversaw the arbitral proceedings. 120 If one party seeks to enforce an award and the other seeks to have the award set aside, the competent People’s Court shall determine to delay the enforcement procedures until the application for setting aside the award is resolved.

A party may petition to the Intermediate People’s Court within six months after receiving a domestic award to have it set aside. When filing a motion to vacate a domestic award, a party must provide evidence that one of the following events has occurred:

- There is no arbitration agreement in place;

- the award’s decisions go beyond the limits of the arbitration agreement or the power of the arbitral institution;

- The creation of the arbitral tribunal or the arbitration proceedings violated statutory procedure;

- The evidence used to make the award was falsified;

- the other party has suppressed sufficient evidence to jeopardize the arbitrator’s impartiality; or

- The arbitrators committed embezzlement, accepted bribes, or issued an award that violated the law while arbitrating the case.

- Unlike foreign-related awards, a domestic award can be set aside after a thorough evaluation of the case’s merits. This could happen if critical evidence is discovered to be insufficient or if the application of the law is determined to be incorrect.

Foreign-related arbitration awards

For foreign-related awards, either party may file an application with the PRC People’s Court within six months of receiving the award. Article 274 of the PRC Civil Procedure Law specifies the grounds for setting aside.

According to article 274 of the PRC Civil Procedure Law, a foreign-related award will be set aside only if and only if the following conditions are met:

- The parties did not include an arbitration clause in their contract and did not afterwards enter into a written arbitration agreement.

- The party seeking to vacate the award was not required to appoint an arbitrator or participate in the arbitral processes, or the party was unable to express its opinions for reasons beyond its control.

- The formation of the arbitral tribunal or the arbitration proceedings did not follow the applicable arbitration rules; or

- The award’s decisions go beyond the limits of the arbitration agreement or the power of the arbitration institution.

- The award may also be set aside if the PRC People’s Court deems that carrying it out would be against public policy.

In an application to set aside a foreign-related award, the Intermediate People’s Court will only consider whether the necessary procedural criteria were met and will not re-examine the dispute’s merits.

AWARDS RECOGNITION AND ENFORCEMENT:

Domestic and foreign-related prizes given in the PRC:

Procedural difficulties that apply to both domestic and international awards

The PRC Arbitration Law expressly requires the parties to carry out the award. 127 If one party fails to do so, the other party may seek enforcement from the PRC People’s Court in accordance with the PRC Civil Procedure Law.

An application for the enforcement of domestic or foreign-related awards must be filed with the Intermediate People’s Courts within two years of the date on which the losing party was ordered to comply with the provisions of the award. 128 In addition to filing the enforcement application, the party requesting enforcement must produce the original award, arbitration agreement, and supporting documents. 129

To avoid contradictory decisions concerning the setting aside and non-enforcement of an award in the same case, where an application to set aside an award has been rejected by the competent court, 130 the enforcing court cannot refuse to enforce such award on the same ground(s) on which the earlier court rejected the application to set aside the award. 131

As discussed in paragraphs 2.3.7 and 2.3.8 above, domestic and foreign-related arbitration organizations may both render domestic and foreign-related awards if the parties agree. With the removal of the distinction between the jurisdiction of domestic and foreign-related arbitration institutions, the underlying nature of the dispute, rather than the identity of the arbitration institution administering the arbitral proceedings, is now the key consideration for the enforcement of an award in the PRC.

Domestic award enforcement

Domestic awards can only be rejected enforcement by the enforcing court if the provisions of article 63 of the PRC Arbitration Law (in conjunction with article 237 of the PRC Civil Procedure Law) are followed. The following are the grounds for withholding domestic awards:

- the parties failed to include an arbitration clause in their contract or failed to achieve a written agreement on arbitration;

- the issues decided in the award are beyond the boundaries of the arbitration agreement or the limits of authority of the arbitration institution;

- The creation of the arbitral tribunal or the arbitration procedure does not follow the statutory arbitration procedure;

- The evidence on which an award is based is contrived;

- The opposite party to the dispute hides critical evidence significant enough to undermine the impartiality of the arbitral institution’s finding; or

- One or more arbitrators acts corruptly, receives bribes or participates in malpractice for personal gain, or renders a law-breaking award.

In addition, a PRC People’s Court may refuse to enforce a domestic award if it considers that doing so would be detrimental to the PRC’s social and public interests. If the competent Intermediate People’s Court refuses to enforce the award, the matter must be submitted to the Higher People’s Court.

The final decision is made by the Higher People’s Court. However, if the parties are from different provinces, the Higher People’s Court must transmit its rejection to the Supreme People’s Court and issue a judgement based on the Supreme People’s Court’s opinions. 135 This means that from 2018, a reporting method similar to that for foreign-related and foreign awards 136 has been established for domestic awards, which shows the recent pro-arbitration tendency in the PRC legal system.

Enforcement of foreign-related awards

The grounds for rejecting execution of a foreign-related dispute award rendered by a PRC arbitral tribunal are the same as those for setting aside such an award (as set out in paragraph 10.2.5 above).

If a party seeks to enforce a legally binding foreign-related award and the party seeking enforcement or that party’s property is not located within the territory of the PRC, the party seeking enforcement must apply directly to a competent foreign court for recognition and enforcement of the award.

If the foreign-connected arbitral award is related to a case heard by a People’s Court, the People’s Court has jurisdiction. If the foreign-connected arbitration decision is related to a case resolved by a domestic arbitration institution, the Intermediate People’s Court at the location of the arbitration institution has jurisdiction.

If the competent Intermediate People’s Court declines to enforce the award, this must be reported to the Higher People’s Court, which must obtain approval from the PRC Supreme People’s Court if the award is to be declared unenforceable.

Foreign awards rendered outside the PRC

Where an award has been rendered outside the PRC either by a foreign arbitration institution or an arbitral tribunal that was established on an ad hoc basis outside the PRC and not voluntarily complied with, the party seeking to enforce that award in the PRC will need to apply to the competent PRC People’s Court for enforcement. The competent court for the enforcement of a foreign award is the Intermediate People’s Court at the place of the respondent’s domicile or where its property is located.

The Intermediate People’s Court shall handle the matter pursuant to the terms of any international treaties concluded or acceded to by the PRC, or in accordance with the principle of reciprocity.

An application for the enforcement of a foreign award must be accompanied by a certified copy of the award and arbitration agreement, with Chinese translations thereof that have been verified by a PRC embassy or consulate, or a notary in the PRC.

When a PRC People’s Court reviews a case on recognising and enforcing a foreign arbitral award by referring to the New York Convention, if the defending party to the application claims that the arbitration agreement is not valid, the court shall decide the validity in accordance with the relevant provisions of the New York Convention.

With effect from 22 April 1987, the PRC became a contracting state to the Convention on the Recognition and Enforcement of Foreign Arbitral Awards June 10, 1958 (New York Convention). However, in its Declaration of Accession, the PRC made a reciprocity reservation.

As a result, the PRC is only obligated to recognise and enforce awards made in the territory of another contracting state of the New York Convention. Foreign awards rendered by foreign arbitration instutitions within the territory of the PRC – for example, an arbitral award rendered by ICC in Shanghai – are not eligible for enforcement in the PRC pursuant to the New York Convention.

According to another reservation made by the PRC to the New York Convention, the PRC will only apply the New York Convention to disputes arising out of legal relationships, whether contractual or not, that are considered commercial under national PRC law. To date, this reservation has never been invoked in practice due to the broad interpretation of the term “commercial disputes” contained in the 1987 Circular of the Supreme People’s Court on Implementing the Convention on the Recognition and Enforcement of Foreign Arbitral Awards Entered by China.

Refusing enforcement of a foreign award

Apart from the above limitations on reciprocity and commerciality, the competent Intermediate People’s Court can only refuse the enforcement of a foreign award for the reasons provided in article V of the New York Convention (eg for serious procedural deficiencies or violations of public policy (ordre public) in the PRC). According to the Circular of the Supreme People’s Court on Issues in the People’s Courts’ Handling of Foreign-related Arbitrations and Foreign Arbitrations promulgated on 28 August 1995 (Circular), if the competent Intermediate People’s Court refuses to enforce a foreign award, this fact shall be reported to the Higher People’s Court. If the Higher People’s Court intends to also declare the award to be unenforceable, it must first seek the approval of the SPC.

The Circular was issued to prevent local courts from refusing the enforcement of foreign awards in order to protect the local party. Before 1995, some PRC People’s Courts had refused to acknowledge and enforce foreign awards. The probability of enforcing a foreign award against a PRC individual or a PRC entity was estimated to be approximately 50% during the 1990s, 147 but has since increased significantly. From 1994 to 2015, 67 out of 98 applications to enforce foreign arbitral awards were granted, resulting in a success rate of 68%. From 2005 to 2015, 78 applications were filed. 46 out of the 78 applications were filed between 2011 and 2015. 148

In 2018, a total of 25 cases were filed with the People’s Courts in relation to recognition and enforcement of foreign arbitral awards. Among these, 14 arbitral awards were recognised and enforced; one arbitral award was refused to be recognised and enforced; one application for recognition and enforcement of arbitral award was dismissed; eight applicants withdrew the application for recognition and enforcement of a foreign arbitral award; one application for recognition and enforcement of the arbitral award was transferred to another competent Court by the Court concerned.

As discussed in section 2.1 above, apart from the exceptions for FTZs, the PRC Arbitration Law does not recognise agreements to ad hoc arbitration. 149 However, the PRC Arbitration Law is silent on whether or not an award made in international ad hoc arbitral proceedings (seated outside of the PRC) is enforceable in the PRC

On 3 December 1999, the Beijing Higher Court issued an opinion stating that an ad hoc award is enforceable in the PRC under the New York Convention if the award has been issued in another contracting state to the New York Convention and the law of that state recognises ad hoc arbitration.

Article 16 of the Interpretation provides that the laws agreed upon between the parties shall apply when considering the validity of an arbitration agreement involving foreign interests. In the same vein, article 18 of the Application Law provides that parties may select, by agreement, the law applicable to their arbitration agreements. Accordingly, if the validity of the arbitration agreement is governed by foreign law, the PRC Arbitration Law will not apply when considering the validity of the arbitration agreement. The implication of this is that the restriction concerning ad hoc arbitration will also not apply.

Awards rendered by foreign arbitration institutions within the PRC

An arbitral award rendered by a foreign arbitration institution within the PRC was, in the past, very unlikely to be acknowledged and enforced in the PRC. However, on 22 April 2009, the Ningbo Intermediate People’s Court in Zhejiang Province upheld an ICC award by labelling it as non-domestic, despite the fact that the award was made in Beijing (Ningbo Case). In the Ningbo Case, the court rejected the respondent’s challenge to the validity of an award that had been rendered in favour of a Swiss claimant by an ICC arbitral tribunal seated in Beijing.

The main reason for the court reaching this decision was that the respondent had failed to object to the jurisdiction of the ICC arbitral tribunal prior to the first oral hearing in the arbitration. In effect, the PRC People’s Court upheld and enforced the award, despite the fact that it was issued by an ICC-administered arbitral tribunal seated within the PRC. Together with the Longlide Case and the BNB Case as discussed above in paragraph 1.2.12, it appears that the judiciary is becoming more liberal towards arbitral proceeding administered by a foreign arbitration institution in the PRC.

The court in the Ningbo Case reached its conclusion from a procedural point of view, ie due to the respondent’s failure to challenge jurisdiction at the appropriate stage of the arbitral proceedings, rather than providing substantive reasoning to confirm that an award rendered by a foreign arbitral tribunal within the PRC should be upheld and enforced by a competent PRC People’s Court.

It is still too early to conclude whether the decisions of the Ningbo Case, the Longlide Case and the BNB Case signal a change that an award that has been made by a foreign arbitration institution within the PRC will be recognised and enforced in the PRC. It is important to note that although the Longlide Case confirmed the validity of a foreign arbitration institution administering an arbitration that has its seat in the PRC, it was silent on the question of whether a resulting award can be validly enforced.

Further laws and regulations on the enforcement of awards rendered in China by foreign arbitration institutions have to be awaited. Until then, it is still advisable to stipulate in an arbitration agreement that arbitral proceedings that are to be administered by a foreign arbitration institution shall be held outside the PRC.

Enforcement of an award made by the International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes

The PRC has been a contracting state to the Convention on the Settlement of Investment Disputes between States and Nationals of Other States (Washington Convention) since 1993. 150 The Washington Convention created the International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID). According to

Artcile 54 (1) of the ICSID Convention, Regulations And Rules (ICSID Convention), “each Contracting State shall recognize an award rendered pursuant to this Convention as binding and enforce the pecuniary obligations imposed by that award within its territories as if it were a final judgment of a court in that State.”

Article 54 (3) of the ICSID Convention further provides that enforcement of the ICSID award “shall be governed by the laws concerning the execution of judgments in force in the State in whose territories such execution is sought”. However, the PRC law does not provide specified rules of implementation on how to enforce an ICSID award. Therefore, it is currently unclear whether the PRC People’s Courts will enforce such awards in practice.

A Case for Bangladeshi Companies

Let’s consider a hypothetical scenario to illustrate the relevance of CEITAC arbitration for Bangladeshi companies:

Imagine a Bangladeshi textile manufacturer entering into a significant international supply contract with a Chinese textile machinery supplier. Despite careful negotiations and a detailed contract, a dispute arises over the quality and performance of the machinery. Both parties are at an impasse, and litigation in their respective countries seems time-consuming and uncertain.

In this scenario, the Bangladeshi textile manufacturer could initiate CEITAC arbitration. The case would be resolved efficiently, with proceedings conducted in English for clarity. The arbitral award would provide a final and enforceable resolution to the dispute, allowing both parties to move forward with their business activities.